Covid has finished what mobile phones started

Any plans for Christmas? A friend asked, as autumn gathered pace. The question, though kind enough, was infuriating. It was summed up in a cartoon another friend sent me, of an anxious-looking man on the telephone: “Are we not coming to you, or are you not coming to us?” How do I know? My Christmas-card order arrived the other day and I stowed them in the cupboard with the twinkly tree-lights. This struck me as the furthest-forward bit of planning I had done since March – and the only bit that was guaranteed to stay in place.

The irony is rich, because at the start of this year I had planned as never before. After the unbearable political stasis of 2019 the very number “2020” had a brisk, organised look to it, like the wheels of a train in motion. On my desk, in neat plastic folders, I had air and train tickets for Italy and Spain, perfectly synchronised. On my mantlepiece (showily) were tickets for Glyndebourne and the Brighton Festival. Of these, the only survivor by July was a booking for a b&b along the coast which I had moved so many times, shifting it steadily through the months, that when I eventually got there I had made no further plans for my visit, beyond aimless wandering and scribbling.

Autumn is traditionally my favourite season, the time (even more than New Year) for fresh starts and casting forward, the smart cut of winter school uniform after those hideous summer frocks, the nipping compulsion of the air. Well, schools are back and parliaments reassembled, but that agreeable cranking-up of the world has not occurred.

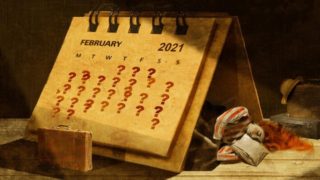

Friends who disappeared briefly in the summer have now retreated longer-term into their unvisitable flats. The schemes that were allowed to drift in heat and idleness are still drifting, and the diary pages are almost blank. November and December contain one hoped-for booking (along the coast again), one blood test (great!) and one Zoom meeting. All are in pencil and have question marks, for ink is much too certain. As a musician said the other day, talking of future engagements, “None of this may happen, or all of it may.”

There’s a part of me that mocks planning. I know that even in calm, predictable times it may all be rendered useless by a bolt from the blue or a runaway bus. I mock the Five-Year Plans of autocratic regimes, with their smack of military music and proud workers marching off to steelworks; I groan, as everyone does, at the readiness of governments to promise some transformation by 2035 or 2050, kicking a project through mile after mile of long grass.

But more modest plans are hopeful, motivating, important. They are like trig points in a landscape, around which time can shape itself. A well-planned day springs me out of bed; an unfocused one makes me linger unhealthily under the duvet. A writing project with a self-imposed deadline, gradually structuring itself with titles and illustrations, is meat and drink to me; time without one is spent searching, like a hen scratching vainly for grain.

In normal years a scattering of grand occasions on certain dates gleam from the calendar like beacons: incentives to get my hair looking smart, lose weight, buy new clothes. The new clothes still beckon, but what for? Nothing on my calendar calls now for this beautiful embroidered jacket or those smart black trousers with a glittery belt. I might as well wear jeans and a t-shirt, my wardrobe as unarranged as the rest of my life.

Plans are like trig points in a landscape, around which time can shape itself

When lockdown first threatened I joined the great craze of planning: bag after bag of dried beans and four replacement toners for my printer. I drew up menus to plan the use of every cabbage and piece of cheese. It was as if the virus could be kept at bay by sheer organisation. When these constraints were eased a little the crisis mode faltered, but no “normal” planning filled the gap. It can’t. When I try to think into the future, I soon turn away. It’s just a blur.

Covid is not the only culprit behind the killing of plans. Well before it, mobiles were making fixed arrangements redundant. A plan to meet at Piccadilly Circus at 6pm would see me standing there, expectant, on the dot but the other party strolling somewhere in Soho, unconcerned, chatting to me as they strolled, suggesting I could walk towards them and we’d be bound to meet, as if set times and places had gone out of fashion. That sense of happenstance, of floating and effortlessly broken arrangements, saw a lot of short-term planning disappear. Now it afflicts the long term, too.

One obvious casualty of the virus has been spontaneity: the kiss, the embrace, the sudden visit, street-stall snacking, impulsive travelling, shelf-browsing. With its antithesis, planning, largely gone too, it’s no wonder that at times we hardly seem to know where, or what, or who we are. But at least I’ve bought the Christmas cards.

ILLUSTRATIONS: ANTONELLO SILVERINI

BY ANN WROE/The Economist