Unpicking the causes of gaps in health outcomes requires better data than most countries currently collect

“I STOPPED COUNTING how many people I knew from my community,” says Marina Del Rios, a doctor in an emergency ward in Chicago, of the flood of desperately ill covid-19 patients. Infection rates among Latinos in Chicago are double those of the city’s African-Americans and triple those of whites. Of the city’s 15 worst-affected zip codes, 11 are predominantly Latino.

In the few countries that collect and publish such data, it is clear that covid-19 has hit ethnic minorities harder than whites. That is in part because the disease disproportionately affects those in jobs, such as security guards and supermarket staff, where ethnic minorities are over-represented. But it is also because of racial disparities in health. Doctors have long argued about the extent to which those disparities are the result of broader inequalities compared with other factors, such as racism or biology. Covid-19 has thrown those questions into stark relief.

Health outcomes differ for racial and ethnic groups. In Brazil people of colour can expect to live three years fewer than white people. In America, where the black-white health gap is at its narrowest ever, black men still live for four-and-a-half fewer years than their white counterparts. Covid-19 has magnified such differences.

It has hit ethnic minorities particularly hard. In Britain all non-white groups (except Chinese women) have been more likely to contract and to die from covid-19 than whites. Trends are similar in America. Disparities are worst among the working-age population. In America a 40-year-old Hispanic person is 12 times as likely to die as a 40-year-old white person, according to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington. Black Americans are nine times as likely to do so.

America and Britain are unusual in collecting and publishing detailed data about health and race or ethnicity. Some countries, such as France, outlaw it. Nonetheless a similar picture is emerging elsewhere. In São Paulo, Brazil’s richest state, black people under the age of 20 are twice as likely to die from covid-19 than their white counterparts. Sweden tallied deaths early in its epidemic and found that those born abroad were several times more likely to die than those born in Sweden.

Professor Sir Michael Marmot, an epidemiologist, writes about how people’s health is determined by social factors. The debate about covid-19 reminds him of 19th-century America, when northern doctors attributed higher rates of tuberculosis among black patients to poverty; southern doctors thought it was genes. “When social conditions improved, tb plummeted in both groups,” he says, “and we learnt that it was overwhelmingly social.”

How rich or well educated people are or what jobs they do is a strong predictor of health. It is the primary driver of racial health inequities. People who suffer more deprivation, which minorities often do, have poorer health and shorter lives. “There’s long been an excessive focus in America on health care as the determinant of health,” says Lisa Angeline Cooper, who researches racial health disparities at Johns Hopkins University.

West Garfield Park is one of the poorest, fastest-depopulating neighbourhoods of Chicago. Many houses, shops and factories are boarded up or abandoned. Fear of gun violence keeps children indoors. Africa Food and Liquor and Quick Food Mart offer few fresh vegetables—mostly cabbage—but shelves stacked with sweets, fizzy drinks and booze. People assume most black deaths in Chicago are the result of gun violence, but the primary cause of early death in neighbourhoods like these is heart disease, says David Ansell, a doctor at Rush University Medical Centre. Across America black men under 50 are twice as likely as white men to die of heart disease.

In Brazil skin colour is a good proxy for social factors too, says Fatima Marinho, an epidemiologist in São Paulo. Sandra Maria da Silva Costa lives in a favela in Rio. She is 46 “but I look 56.” Even before catching covid-19 in April, she suffered from a litany of health problems, including in her lungs. Her lungs worsened in September when, after stealing some meat and milk, she spent a month in prison, where she received no health care. Both her parents died last year. They never spoke about racism or exclusion, says Ms da Silva Costa; they simply accepted that they would not get proper health care. “We’re black, poor and jobless,” she says. “We’re invisible.”

Wealth and education matter even in countries where people are treated more fairly. People who live in the areas of England and Wales that count among the most-deprived 10% are twice as likely to die of covid-19 as those in the least-deprived areas. All ethnic minorities except Indians and Chinese are more likely to live in such places than whites. Pakistanis are more than three times as likely as white Britons to do so and Bangladeshis twice as likely.

Two things help explain the disproportionate impact of covid-19 on ethnic minorities. First, and most important, they are more likely to be exposed to the virus. In many Western countries minorities are more likely to work in jobs that put them into regular and close contact with the public, increasing their risk of infection. They are also more likely to live in cities, in deprived areas and in crowded, multigenerational homes, all of which increase their exposure. Second, when they catch the virus they are more likely to die of it than white people. That is probably because pre-existing conditions, such as diabetes and heart disease, which increase the risk of dying of covid-19, are more common among ethnic minorities.

A virus that discriminates

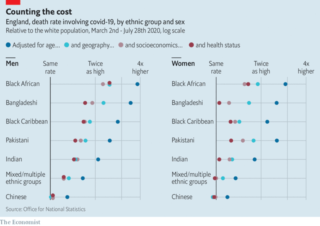

Such factors go a long way to explaining the disproportionate impact of covid-19 on non-white people in Britain, according to the country’s Office for National Statistics. But not entirely. Bangladeshi men are three-and-a-half times more at risk of dying of covid-19 than white men of the same age. After controlling for geography (this group is twice as likely to live in densely populated areas), this ratio fell to 2.3. After controlling for factors such as poverty and exposure at work, it fell to 1.9. But even after including self-reported health concerns and pre-existing conditions, their risk was still almost one-and-a-half times that of white men of the same age (see chart).

Even Sir Michael concedes that it is increasingly clear that socioeconomic conditions do not fully explain racial disparities in health. In a recent report he and colleagues found that in several countries in the Americas, such as Colombia and Brazil, the worse health of black people cannot fully be explained by conventional socioeconomic measures. The differences are greater for men than women in America. For black American women the life expectancy gap narrows significantly when controlling for education and income. “But for men a sizeable unexplained gap remains,” says Sir Michael. Some of that disparity can be explained by high homicide rates among black American men. They are also more likely to die of aids (though this affects relatively few men, it kills them when they are young and so has a significant impact on average life expectancy). But that does not fully explain the gap.

Puzzling patterns

Cancer is a good example of a disease the prevalence of which cannot be explained by socioeconomic factors alone. In Britain black people have much higher rates of stomach and prostate cancer than other groups. Asian women are more likely than any group to contract mouth cancer. South Asian women are the least likely to get cervical cancer. White Britons have the highest rates of cancer overall. Understanding why certain groups are more likely to get different cancers hints at the complex interaction of social factors and biology that may be at work.

People’s risk of dying of particular diseases tends to reflect underlying conditions that make them more vulnerable, their access to a doctor or the treatment they will receive. Black women in America are no more likely than white women to get breast cancer but much more likely to die from it. Ethnic minorities made up 11% of covid-19 hospital admissions in Britain in May but 36% of those receiving intensive care. Hospitalised South Asians were the group least likely to survive, whereas there was no difference between black and white people, according to one study.

Disparities exist in other areas, too. Few things predict more accurately whether a woman will survive childbirth than the colour of her skin. In America black women are three times, and native Americans two-and-a-half times, as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as white women. Even after controlling for education, differences persist. Covid-19 could compound this. In Britain’s first wave 55% of pregnant women hospitalised with the virus were from black and other ethnic-minority groups (they represent 14% of the population). In Brazil black pregnant women hospitalised with covid-19 have been around twice as likely to die as white ones.

What might explain such gaps? First, pre-existing conditions. In the rich world the leading cause of death related to childbirth is heart disease, responsible for over a third of deaths. Prevalence is higher among black women. Second, access. In America 89% of white women receive prenatal care in their first trimester, compared with 75% of black women. This means missed opportunities for early diagnosis of problems in pregnancy. Third, unequal treatment. In some Brazilian hospitals black and brown women are treated as though they are of lesser value, says Dr Marinho.

Many indigenous people in Brazil are reluctant to go to hospital at all. Previous interactions and “years of delays [in getting hospital appointments] generated a lack of trust, a lack of hope,” explains Elivar Karitiana, of the Karitiana tribe, who works for the indigenous health-care system in the Amazonian state of Rondônia. When his uncle, a healthy 56-year-old, became very ill with covid-19, he ended up in hospital in Porto Velho, the state capital and died. Villagers insisted “the doctors killed him” by putting in a breathing tube, says Mr Karitiana. He now worries about a second wave in the village. Since his uncle’s ordeal the tribe has become even more sceptical.

A problem everywhere

Even Britain, where health care is free, has disparities. Some groups make less use of programmes meant to catch health problems before they become more serious. Several studies have shown that women from ethnic minorities in Britain make less use of cervical screening than white women. They were more likely than white women to say (wrongly) that they were not at risk or to say they were scared of what might be found, or embarrassed or fearful of being seen by a male doctor.

Governments are belatedly working to ensure that efforts to stop covid-19 reach all people: putting testing centres in places particular groups will visit, for example, such as churches. At the start of the pandemic Latinos in Chicago, many undocumented migrants, made less use of testing centres than others because they were afraid of the authorities who ran them.

Awareness of cultural barriers will be crucial when rolling out covid-19 vaccines. Culture Care, in California, matches black patients with black medics. A study by America’s National Bureau of Economic Research in 2018 found that black men seen by black doctors consented to more invasive preventive screening procedures (blood tests, for example, and injections), and more of them, than those seen by non-black ones.

But there is also evidence, mostly from America (which has good data), that people of colour simply receive worse medical care. When a black man enters a hospital with a heart attack he is about a third less likely than a white man entering a similar hospital with similar symptoms to receive a treatment called balloon angioplasty within 90 minutes (this timing is a key quality indicator). Studies show that black patients get less pain medication too (so much so that it is thought to have helped keep opioid addiction rates among black Americans well below those of whites).

Pain in black people is underestimated compared with pain in white people. An experiment by the University of Virginia found that around half of a sample of white medical students held some false beliefs about biological differences (that black people have thicker skin, for example). Such views were associated with underestimating and undertreating black pain.

New research looks at the health effects of chronic exposure to discrimination. The idea is that living in a racist society increases stress hormones for minorities and damages their health. Living in a racist environment can harm the health of all black people, even those who do not directly experience racism, says Delan Devakumar, at the Institute of Global Health at University College London. “This is akin to other environmental risk factors for health, such as high levels of air pollution,” he adds.

And yet all this does not fully explain the racial disparities seen with covid-19. This is apparent from work done using the Biobank data set, an exceptionally detailed medical database of the lives and health of hundreds of thousands of British people. When using these data to account for socioeconomic status, lifestyle, vitamin D levels and pre-existing health disparities, they still do not explain all the differences.

Known unknowns

Some are now calling for a deeper look into the possible genetic contributions to covid-19-related health disparities. Naomi Allen, Biobank’s chief scientist, says population-level differences in the genetics of the immune response to sars–cov-2 might increase the risk of hospitalisation and death. Asking questions about genetic factors, though, is tricky. Some fear they will distract from the big and important socioeconomic factors. Others think they are a red herring because the races that humans recognise are socially determined, rather than having real genetic underpinnings.

And yet it is true that different populations from different environments and places can have different variants of the same genes. In malaria-ridden parts of the world, natural selection has led to an increased prevalence of a gene that causes blood cells to form an odd sickle shape (which helps explain why over 90% of sufferers of sickle-cell disease in America are black). This protects against malaria.

Evolution has also tinkered with immunity. In some areas, presumably where ancestral levels of pathogens were higher, the immune system is more reactive. That is useful when fighting off illness, but having an overactive inflammatory system can also trigger chronic troubles such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. These then put people at greater risk for other health conditions. There is evidence that those of African ancestry have a stronger inflammatory response than Europeans.

A set of genes inherited from Neanderthals influences which patients get severe covid-19. They are found throughout European populations at a low frequency. They are, though, particularly prevalent in South Asia. Bangladeshis carry the highest frequencies of these genes, a factor worth exploring when considering why Britons of Bangladeshi origin have had such high death rates of covid-19. These genes are absent in black people—who have a high infection risk, too. This demonstrates just how multifactorial disease can be.

According to research conducted by Raj Chetty, an economist, and others, the life-expectancy gap between rich and poor Americans has been rising even as the racial one has been declining. This suggests that in America race is becoming a poorer predictor of health outcomes than income or deprivation. The disparities change. But the world cannot stop counting.

By The Economist