Restrictions on travel have disrupted a deeply important cultural practice for many Black residents in Cape Town: returning the body for burial hundreds of miles home in the Eastern Cape province.

KHAYELITSHA, South Africa — In ordinary times, there would have been no question where Zinzile Mweli would be buried: alongside his ancestors in the village where he was born.

But when Mr. Mweli, a minibus taxi owner, died last month from Covid-19 in Cape Town, 600 miles west of his hometown, his family was forced to confront a new predicament for many Black South Africans during the pandemic: Would it be possible to return his body home for a funeral, accompanied by his loved ones from Cape Town?

In March, South Africa imposed one of the world’s most severe lockdowns in response to the coronavirus, restricting travel between provinces. This disrupted a deeply important cultural practice for many Black residents in Cape Town: returning the bodies of family members to the neighboring Eastern Cape province for burial.

The new rules around travel for funerals are so complex, and add such extra expense, that they have become practically insurmountable for many families, according to funeral directors and community leaders in Cape Town.

For some poorer families, the rules are forcing a choice between breaking tradition and breaking the law.

“It’s a big trauma,” said Chris Stali, the director of a funeral parlor in Khayelitsha, the informal settlement on the outskirts of Cape Town where Mr. Mweli lived while working in the city.

Zinzile MweliCredit…via the family of Zinzile Mweli

While South Africa is now attempting to reopen, and easing some restrictions, the rules around funerals are still in place. Attendance at funerals is capped at 50, and overnight vigils and body viewings are banned.

The regulations have been felt especially acutely in Cape Town, the initial epicenter of the country’s outbreak. South Africa now ranks 14th in the world for coronavirus cases, and is experiencing an enormous rise, with more than 13,500 cases reported in 24 hours on Thursday. To date, the country has reported more than 224,000 cases and more than 3,600 deaths — and about 60 percent of these deaths were in the Western Cape province, where Cape Town lies.

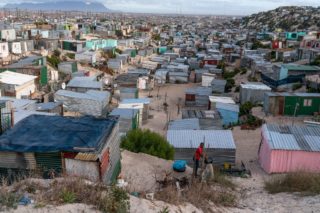

Social distancing in townships like Khayelitsha is all but impossible — entire families often share single, one-room shacks, packed tightly beside their neighbors — and infections are continuing to climb here.

But infections are also surging in other provinces — in Gauteng, where Johannesburg is, cases recently doubled within eight days — and experts warn that the rise in deaths may pose similar problems for families there who wish to bury loved ones in rural areas.

The township of Khayelitsha, on the outskirts of Cape Town, where Mr. Mweli lived, 600 miles from his home town.Credit…Nic Bothma/EPA, via Shutterstock

The majority of Khayelitsha’s approximately 400,000 residents are Xhosa people from the Eastern Cape who return home for holidays and major life events — and eventually, to be buried.

But health officials fear that mourners from the city will carry the virus to rural areas that are among the most vulnerable in South Africa.

So now, after a loved one’s death, relatives living in Cape Town must apply for travel permits with the police, and only close family members are given permission: no cousins, no close friends, no neighbors.

There have also been changes to how a body is moved that have made the cost prohibitive for poorer families. Before the outbreak, it was common for mourners to pack together closely in a minibus and to tow the body behind in a trailer.

Now, the corpse must be transported in a separate vehicle, attended by a certified undertaker, meaning that cash-strapped families must hire at least two vehicles.

To get around the restrictions, some mourners are forging travel permits, bribing officials or taking long backcountry routes to avoid roadblocks.

“If there is a regulation that will interfere with cultural or spiritual beliefs,” said Kenny McDillon, a pastor who operates a funeral repatriations service in Cape Town, “the ordinary citizen will become a criminal.”

A checkpoint in Cape Town, set up to prevent the spread of the virus.Credit…Nic Bothma/EPA, via Shutterstock

Mr. Mweli tested positive for the virus on May 4, as community transmission of the virus began accelerating. He was dead within a week, at age 68.

His family “didn’t even consider” burying him in Cape Town, said Mr. Mweli’s niece, Fezeka Nkubo. As in many African cultures, they believed it essential to bury Mr. Mweli beside his ancestors, smoothing his passage into an afterlife where spirits of the dead mingle with the living.

This burial tradition acquired additional significance in South Africa under white rule, when the migrant labor system drew Black workers into cities but forbade them from settling permanently there, saidProfessor Leslie Bank, an anthropologist at the Human Sciences Research Council of South Africa.

This cemented the practice of repatriated funerals and gave rise to an entire industry designed to facilitate them, from insurance plans to transportation services.

“Communities are very distressed at the idea of burials not being fulfilled,” said Dr. Thobile Mbengashe, the head of the Eastern Cape health department. “Even if you block the road, they’ll still want to come.”

Dr. Mbengashe acknowledged that several bodies had been “smuggled through the system” after the restrictions were imposed.

People waiting outside a testing clinic in Khayelitsha, South Africa, practice social distancing. Nardus Engelbrecht/Associated Press

The Western Cape and Eastern Cape provincial governments have been weighing even tougher restrictions, including further limiting how many people can travel to funerals, which is currently capped at 50.

“When the curve starts going up, we can’t have that many people traveling,” said Alan Winde, the leader of the Western Cape government. “It’s not a comfortable discussion to be having,” he added. “To be saying, at some stage, you can’t bury people at home.”

The wrenching effects of the national regulations already in place are clear to Mr. Stali, the undertaker.

On a weekend in June, two mourning families he was working with from Khayelitsha were turned back at a roadblock near the provincial border between the Eastern Cape and the Western Cape for not complying with regulations requiring people to travel in separate vehicles from the body.

Mr. Stali hastily arranged funerals for the families in Cape Town, instead. “I had to give them the cheapest funerals I could provide,” he said.

Dozens of other families have resorted to burying in Cape Town, said Mzanywa Ndibongo, the chairman of the Khayelitsha Health Forum, a community organization. “It is not their wish to bury here,” he said, “but because of the regulations, they are forced to do that.”

A cemetery in the Gugulethu township outside Cape Town. Sydelle Willow Smith for The New York Times

The experience of Mr. Mweli’s family shows just how daunting the regulations can be.

After he died in May, his family struggled for days to get travel permits. First they needed a letter from the hospital confirming his death. Then they had to apply for a death certificate from the national home affairs department — but officials were unduly afraid of contracting the virus from the paper with Mr. Mweli’s fingerprints, a problem that took days to resolve.

Finally, the family lined up for hours at the police station for travel permits. The national regulations state that Covid-19 victims are supposed to be buried within three to seven days; by the time the family received their permits, more than a week had passed.

Nevertheless, they were able to travel home to the village of Xonxa, where Mr. Mweli had met his wife nearly 50 years ago and from where they left for Cape Town in 1985. The family rode in one of Mr. Mweli’s taxis, to save on travel costs, with an undertaker transporting the body separately.

Bodies of Covid-19 victims are required to travel directly to the grave, and local health officials took possession of the coffin when it reached the village.

The family waited to be called for the funeral. But later that day, they found out from local officials that Mr. Mweli had been buried without them.

“We don’t even know if it was the right coffin,” said Ms. Nkubo, Mr. Mweli’s niece.

The family, now back in Cape Town, believes that his spirit is not at peace, Ms. Nkubo said — and that this, in turn, will bring them misfortune.

As soon as possible, they plan to return once more to Xonxa, where they will exhume Mr. Mweli and lay him to rest.

FEATURED IMAGE: Undertakers carrying coffins at the end of a funeral for coronavirus victims in Cape Town, South Africa, this month. Marco Longari/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

The New York Times