A guide to seasonal selling, from goats to gizmos

Tradition, like Leonardo DiCaprio’s girlfriends and parts of downtown Warsaw, is rarely as old as we might prefer. That goes double for Christmas – a Pagan festival, later retooled for God, that became the Western year’s peak of pleasure and indulgence because 19th-century capitalism and civic culture gave it the space to do so.

Britons pioneered this shift. They promoted Christmas as a universal holiday, and legislated for it in the 1830s. (America followed in 1870.) They invented Christmas cards and crackers, pulled new-year gift-giving rituals forward by a week, popularised forgotten carols, created Scrooge as a punishment for dissenters and let these images and commodities circulate through another of their creations: advertising-driven mass media.

At this time of year, we should think of their work and reflect on the historical shallowness of some of our most profound seasonal pleasures. Advertising gives us a place to do that, with its appeal to magic and desire, and the clues it contains about the origins of our habits.

We can’t gaze over the shoulder of Thomas Nast, an American commercial artist who invented the Republican elephant and the Democrat donkey, and came up with the idea that Santa Claus works in a polar toy factory staffed by elves. But we can trace the progress of his work through culture and observe how his successors – some of them noted here – developed his imagery until we forgot its origins. And then we may see them. On billboards, in tv adverts, campaigns and schemes and memes. The ghosts of Christmases past, haunting our feelings and our transactions.

The real thing The taste of Christmas past

The ambition was to defy nature, like the man in the Huysmans novel who encrusts his pet tortoise with rubies. The tortoise in the book died, but Coca-Cola conquered Christmas and the world. Its standard-bearer was Haddon Hubbard “Sunny” Sundblom, a Michigan-born commercial artist who painted himself as Santa Claus in 1931 for a campaign aimed at persuading Americans to adopt a perverse and unnatural habit – knocking back ice-cold soda in brass-monkey weather.

“Thirst knows no season”, was the slogan. The ads even suggested that instead of a glass of milk or cream sherry, Father Christmas might appreciate a bottle of Coke left on the hearth. That didn’t catch on, but Sundblom’s images generated a mythology of their own.

It’s often claimed that Coca-Cola invented our paunchy, jolly, grandfatherly Santa and dressed him in its own red-and-white corporate livery and in so doing relegated older, ancestral figures in snow-white fur or conifer green, who were displaced like forgotten brands of fizzy drink. That’s not the case. Coca-Cola has blotted out the memory of Candy-Cola, Kos-Kola and Klu Ko Kola – a variety marketed at white supremacists – but the rubicund Santa was standard before Sundblom. Even the power of capitalism has its limits.

Silent fight The gifts that keep on being given

The Christmas issue of the satirical magazine Private Eye always contains a double-page spread of adverts for novelty gifts nobody would ever want: a “Handmaid’s Tale” bedside lamp, the hs2 stairlift or “Encyclopaedo Britannica”, a multi-volume index of British sex offenders.

Yet these impossible objects invoke something all too real – the Christmas advertisement that seems to exist purely to measure the poverty of the relationship between giver and recipient. This image of Santa staffing the North Pole Frigidaire hotline may look superficially bright and festive, but it is a trap to lure men into marriage-killing misjudgments.

The history of American advertising glitters with stuff like this. Pictures of husbands proffering electric toasters like myrrh, women experiencing prophetic visions of sewing machines, children imploring Santa to put a new Hoover for mummy under the tree. A Christmas litany to which the best response would seem to be: “Darling, you really shouldn’t have.”

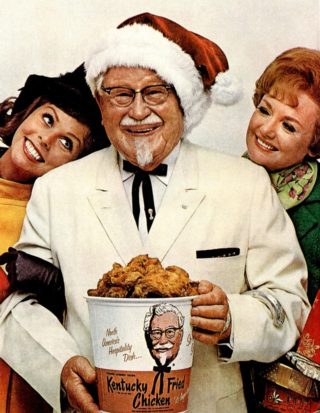

Kentucky Fried Christmas Finger lickin’ feasts

Christmas Day isn’t a day for fast food. On December 25th the catering process should be slow, elaborate, ritualised and provide evidence for the central claims of R.D. Laing’s book “Sanity, Madness and the Family”.

But to imagine otherwise, to picture, in the dreamspace of advertising, the family gathered around the Bargain Bucket, remains a worthwhile endeavour for dipping-sauce and drumstick-mongers. In this example from the 1960s, Colonel Sanders bears a waxed grail of Yuletide hot wings to his beaming wife and daughter (or mistress).

We know, though, that even kfc’s commanding officer wouldn’t consider this a serious serving suggestion on Jesus’s birthday. The company’s Christmas tv campaign in 2013 pushed the idea harder, depicting a disparate gang – kids, frazzled parents, a department-store Santa besmirched with child urine – sharing a boneless feast and singing a knowingly preposterous “We are the World” type anthem: “One of everybody’s vices/Is the lemon, herbs and spices.” How does this add value to the brand? Christmas is the only day of the year this joke works. On every other, deep-fried poultry is fair game.

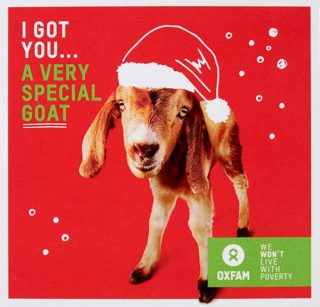

The goat of Christmas presents A bleat is for life

Before the 19th century Christmas charity was a ritual of high privilege through which bishops distributed coal to the diocesan poor and toffs invited local urchins for dinner up at the hall. The Victorian middle-classes democratised all that, taking their cue from Scrooge’s last-minute turkey dash in “A Christmas Carol”.

That practice is revised in this ad from the fat years before the global financial crisis. Oxfam exhorts its supporters to send things to the needful Cratchits of the developing world. But they’re also extending the circuit of patronage to your friends and family.

Maybe your loved ones would have preferred cash or a crème brûlée torch. Maybe they simply feel judged for the volume of stuff already under their tree. If not, a bargain can be struck between giver and gifted, allowing anxieties about unearned plenitude to be assuaged. A toilet you’ll never use is being dug in a village you’ll never visit. A goat you’ll never see is standing in a yard where you’ll never sit. And should the Ghost of Christmas Future visit, you will be shown not your own neglected tombstone but a photograph of a cistern, somewhere in Africa.

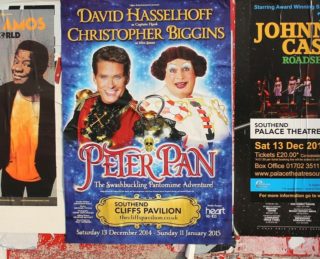

Oh yes he did Nothing like a dame

There are two types of pantomime. Vulgar commercial enterprises creaking with soap and sports stars, “X Factor” runners-up and unlikely screen personalities (Henry Winkler, perhaps, or Britt Ekland, or in this case, the Hoff). The second kind are gentler, more literary productions uncluttered by celebs. These position themselves as “traditional” and mention the Brothers Grimm – or maybe Angela Carter – in the programme notes.

The uninitiated may notice nothing, but this is one of the bitterest fronts in the British class war. My feeling – and here I may reveal a prejudice – is that the latter appeals to middle-class parents, and the former is the true and proper carrier of the tradition, which has always used fairy-tale plots as a vehicle for topical gags, cross-dressed uproar, preposterous spectacle, stunt casting and sexual innuendo that the kids in the audience must pretend not to understand.

Some ignorance, though, is unfeigned. British critics of the 1990s who tutted about the heavyweight boxer Frank Bruno taking Christmas work from proper stage actors didn’t know that his bare-knuckle forebear, Daniel Mendoza, had been booked for a production of Robinson Crusoe in Birmingham in 1791. A boxing day of a different kind.

Oh yes he did Nothing like a dame

There are two types of pantomime. Vulgar commercial enterprises creaking with soap and sports stars, “X Factor” runners-up and unlikely screen personalities (Henry Winkler, perhaps, or Britt Ekland, or in this case, the Hoff). The second kind are gentler, more literary productions uncluttered by celebs. These position themselves as “traditional” and mention the Brothers Grimm – or maybe Angela Carter – in the programme notes.

The uninitiated may notice nothing, but this is one of the bitterest fronts in the British class war. My feeling – and here I may reveal a prejudice – is that the latter appeals to middle-class parents, and the former is the true and proper carrier of the tradition, which has always used fairy-tale plots as a vehicle for topical gags, cross-dressed uproar, preposterous spectacle, stunt casting and sexual innuendo that the kids in the audience must pretend not to understand.

Some ignorance, though, is unfeigned. British critics of the 1990s who tutted about the heavyweight boxer Frank Bruno taking Christmas work from proper stage actors didn’t know that his bare-knuckle forebear, Daniel Mendoza, had been booked for a production of Robinson Crusoe in Birmingham in 1791. A boxing day of a different kind.

Consumer culture turned Christmas perfume into a tribute, a love-test, chemical evidence of desire and disposable income. Reassuringly expensive advertising reinforces the message, and France remains the natural zone of action. Lancôme gave Julia Roberts the freedom of Paris in a backless frock studded with 700 Swarowski crystals. Coco Chanel propelled Keira Knightley down the Seine in a speedboat, watched by a desiring secret agent.

The most lavish production of all couldn’t quite bear to admit it was an advert. “No.5 the Film “(2004) was a 180-second romantic epic which, like “Moulin Rouge!” in 2001, put Nicole Kidman under the eye of Baz Luhrmann and made her the heroine of her own sensual world. One that promised: you, too, can always have Paris. In bottled form, and at a price.

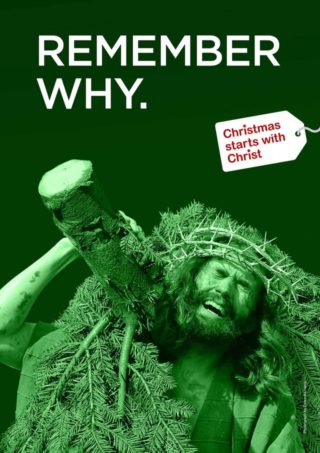

The realms of glory Putting Christ back into Christmas

Victorian legislators and capitalists brought the modern Christmas holidays into being. The “Christmas Starts with Christ” campaign, launched in 2009 and partly funded by the Evangelical Christian Alliance in Britain, insists that “strong cultural and secular forces are at work” to prevent Jesus from getting more of the credit.

It’s hard to track the moment at which it became axiomatic to assert that commerce had pushed the Son of God to the side of his own festival. But this ad from 2017 is a bright green landmark. And lo, behold its semiotic thickness: the gift tag, the Crown of Thorns reminding us that the baby in the manger is father to the man scourged and crucified by Roman justice.

The cut pine tree plays the part of the One True Cross, but symbolises, perhaps, the burdensome pagan weight of baubles and candles and gingerbread dumped on British culture by Prince Albert. But that allusion makes it easier to turn the argument around. The tree may not be a burden but a support. Something old and deeply rooted, here before Him, and providing a canopy under which newer faiths might nest.

War and peas Off their trolleys

You now have to be quite old to remember a Christmas supermarket advert that had anything to say about the price of sprouts. Now, every corporate grocer supplies its own sentimental Christmas number, a seasonal story in which a sad pensioner or a lonely astronaut makes us grateful for what we have: family, friends and several hundred pounds worth of meat, pastry and alcohol booked for click-and-collect.

With the transactional element so obfuscated, there’s more room for argument. Room, sometimes, for a skirmish in the culture war. Sainsbury’s discovered this in Britain in 2014 after it took its customers to the trenches and the Christmas truce of a century before. Critics accused them of beautifying blood and barbed wire and barbarity, despite the blessing of the Royal British Legion.

This year the supermarket has done it again – quite accidentally – by commissioning an ad in which a black dad and daughter have a cute phone conversation about gravy. Racists, it seems, prefer a white Christmas. Their protest inspired a counter-protest: Aldi, Asda, Co-op, Iceland, Lidl, Marks & Spencer, Sainsbury’s, Tesco and Waitrose ran primetime adverts back-to-back with the hashtag #StandAgainstRacism. Another Christmas truce.

images: advertising archives, getty, alamy, oxfam, nicole kidman and rodrigo santoro by baz luhrmann for chanel, dinendra haria/churchads

By MATTHEW SWEET/The Economist

Thanks for the blog article. Really thank you! Want more. Karry Bourke Krutz