The mass inoculation campaign that began in Britain on Tuesday has little precedent in modern medicine.

Britain’s National Health Service began delivering shots of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine on Tuesday, opening a public health campaign with little precedent in modern medicine and making Britons the first people in the world to receive an authorized, fully tested vaccine.

Here’s a guide to some of the basics.

Should I be concerned about the safety of the vaccine in Britain?

Britain’s drug regulator is seen as a bellwether agency, and its decisions often have influence abroad. In the case of the Pfizer vaccine, the agency has said that it did not cut any corners, and undertook the same laborious process of vetting the quality, efficacy and manufacturing protocols of the vaccine — except faster than usual.

Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the United States’s top infectious disease expert, said last week that the British had not reviewed the vaccine “as carefully” as the United States was. But he walked back those comments the next day, saying: “I have a great deal of confidence in what the U.K. does, both scientifically and from a regulator standpoint.”

Who in Britain will get the vaccine first?

Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital in London was among those starting to administer the vaccine on Tuesday. Mary Turner for The New York Times

Doctors and nurses, certain people over 80 and nursing home workers.

Some doctors and nurses have received invitations in recent days to sign up for appointments, with the first shots intended for those at the highest risk of severe illness. The government has indicated that people over 80 who already have visits with doctors scheduled for this week, or who are being discharged from certain hospitals, will also be among the first to receive shots.

Nursing home residents, who had been designated the top priority by a government advisory body, will be vaccinated in the coming weeks once health officials start distributing doses beyond hospitals.

They said they were not able to do so right away because of the ultracold storage requirements of the Pfizer vaccine. The vaccine must be transported at South Pole-like temperatures, though Pfizer has said that it can be stored for five days in a normal refrigerator before being used.

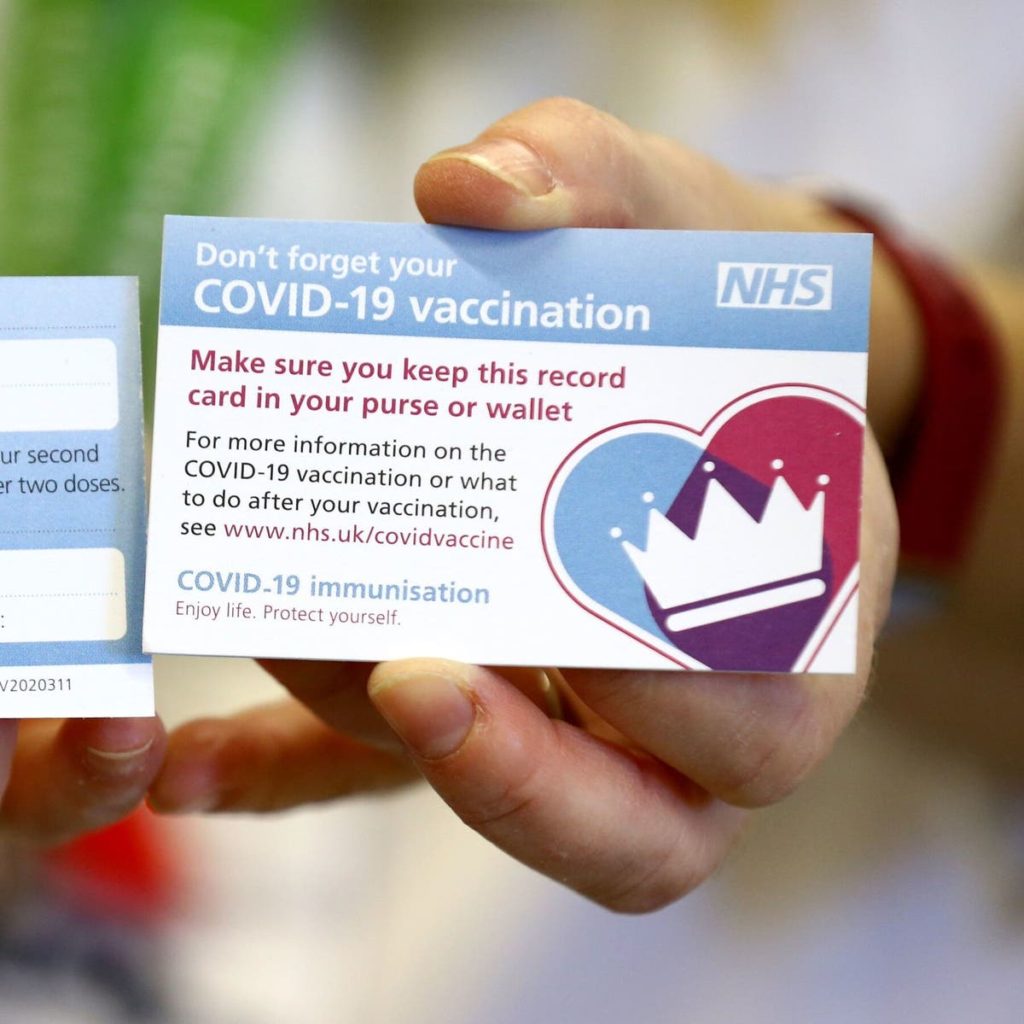

How will the vaccine cards work?

After the first dose of vaccine, patients will receive a card reminding them when they are due for a second dose. Pool photo by Gareth Fuller

British health officials released images on Monday of a small, wallet-size vaccination card. It will hold a record of the date of someone’s first and second dose of the vaccine, which are supposed to be roughly a month apart.

While the images raised fears of a government-mandated vaccine passport program, with the cards functioning as proof of vaccination and a key to traveling and going to events, health officials have indicated that the card will not function that way.

They have compared it to cards already in use by the country’s National Health Service for other two-dose vaccinations, and said it would be useful but not necessary for people to bring it to their second vaccination appointment. The card does not even have space for a vaccinated person’s name, making it impossible to use as proof of someone’s vaccination.

When can I return to normal life after being vaccinated?

Life will return to normal only when society as a whole gains enough protection against the coronavirus. Once countries authorize a vaccine, they’ll only be able to vaccinate a few percent of their citizens at most in the first couple months. The unvaccinated majority will still remain vulnerable to getting infected.

A growing number of coronavirus vaccines are showing robust protection against becoming sick. But it’s also possible for people to spread the virus without even knowing they’re infected because they experience only mild symptoms or none at all. Scientists don’t yet know if the vaccines also block the transmission of the coronavirus.

So for the time being, even vaccinated people will need to wear masks, avoid indoor crowds, and so on.

Once enough people get vaccinated, it will become very difficult for the coronavirus to find vulnerable people to infect. Depending on how quickly we as a society achieve that goal, life might start approaching something like normal by the fall 2021.

If I’ve been vaccinated, do I still need to wear a mask?

In London last week. Andrew Testa for The New York Times

Yes, but not forever. The two vaccines that will potentially get authorized this month clearly protect people from getting sick with Covid-19. But the clinical trials that delivered these results were not designed to determine whether vaccinated people could still spread the coronavirus without developing symptoms. That remains a possibility. We know that people who are naturally infected by the coronavirus can spread it while they’re not experiencing any cough or other symptoms.

Researchers will be intensely studying this question as the vaccines roll out. In the meantime, even vaccinated people will need to think of themselves as possible spreaders.

Will it hurt? What are the side effects?

The Pfizer and BioNTech vaccine is delivered as a shot in the arm, like other typical vaccines. The injection won’t be any different from ones you’ve gotten before. Tens of thousands of people have already received the vaccines, and none of them have reported any serious side effects. But some of them have felt short-lived discomfort, including aches and flu-like symptoms that last less than a day. It’s possible that people may need to plan to take a day off work or school after the second shot.

While these experiences aren’t pleasant, they are a good sign: they are the result of your own immune system encountering the vaccine and mounting a potent response that will provide long-lasting immunity.

Does the vaccine affect fertility?

Lisa McCulloch, center, a clinical educator, speaking to medical staff before the delivery of the first vaccine at the Royal Victoria Hospital, in Belfast, Northern Ireland, on Tuesday. Pool photo by Liam Mcburney

There’s no evidence that it does, and there’s good reason to think that it does not.

Some claims have been floating around the web that coronavirus vaccines can harm a woman’s fertility. Their supposed evidence rests on the fact that most coronavirus vaccines work by creating antibodies that attack the virus’s “spike” protein, and this protein has a minor resemblance to a protein crucial for the formation of the placenta.

But that does not mean that the antibodies generated by coronavirus vaccines would attack a pregnant woman’s placenta. The region of the placental protein that’s similar to the spike is just too short to give the antibodies a grip.

What’s more, the pandemic has brought a lot of evidence against the idea that the vaccine could threaten the placenta. When people get Covid-19, they fight off the coronavirus, known as SARS-CoV-2, by generating their own supply of spike antibodies. In recent months, researchers have carried out a number of studies on pregnant women to see if Covid-19 leads to miscarriages.

“And the consistent message is no, SARS-CoV-2 does not seem to induce miscarriage,” said Dr. Emily Miller, Assistant Professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Northwestern University. “If the placenta isn’t knocked out by antibodies generated from overt infection with SARS-COV-2, it is highly unlikely that it would get knocked out after vaccination.”

FEATURED IMAGE: Katherine Carnegie, a junior doctor, was given the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in Cardiff, Wales, on Tuesday. Andrew Testa for The New York Times.

By Benjamin Mueller and Carl Zimmer/The New York Times