The promises glimpsed in 14 years of the country’s history, between 1863 and 1877, remain unfulfilled

ON APRIL 13th 1873 a group of armed white men rode into Colfax, Louisiana, a town around 200 miles north-west of New Orleans. Included in their number were members of the Ku Klux Klan and Knights of the White Camelia, both terrorist groups devoted to maintaining white rule across the American South. They were coming to seize the courthouse, then occupied by black and white Republicans who claimed victory in a disputed election the year before (Republicans were the party of Abraham Lincoln and emancipation). Republicans called on their supporters, most of whom in Colfax were black, to defend them.

The invaders were better armed, and laid down an enfilade of cannon fire. Some of the defenders fled. They were pursued and shot to death. Around 70 retreated into the courthouse, which the whites set ablaze. The courthouse’s defenders extended from a window the sleeve of a shirt as a white flag. Emerging unarmed, 37 were taken prisoner. After dark, they and other prisoners were marched two-by-two away from the courthouse, told they were going to be set free. They too were shot, and left unburied for days. As many as 150 black Louisianans died that day.

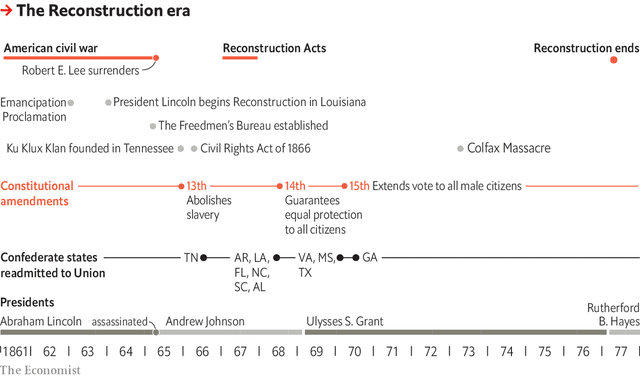

The Colfax Massacre, as it came to be known, was not an isolated incident. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, racist terrorism swept across the South, targeting newly freed black Southerners and the whites believed to be helping them. This violence hastened the end of Reconstruction. Most historians define the period as beginning with the enactment of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, before the end of the civil war, and ending when Rutherford Hayes withdrew federal support in 1877 as part of a political bargain that put him in the White House.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Reconstruction began with unbridled enthusiasm among those who saw, in the defeat of the Confederacy and the end of slavery, a chance to remake the South, and compel America to live up to the promise of its founding documents. It ended in cowardice and compromise. Hayes’s decision led to almost a century of white-supremacist rule across the South, which only began to crumble in the mid-20th century, as civil-rights activists won court cases and pressured Congress and the president to pass and enforce legislation.

Reconstruction tends to get less attention than other foundational periods in American history, such as the founding and the civil war. Perhaps that is because, as an attempt to create an enduring multiracial democracy, it failed. But in the three Reconstruction amendments, and more broadly in the idea that the federal government should act as a guarantor of individual liberties, it planted the seeds of such a democracy. For that reason it remains central to American politics.

Reconstruction was a deeply contested undertaking. For lawmakers and elected officials, it was an attempt to answer a question that neither the constitution nor American history had encompassed. Eleven states—in order of their secession, South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee—seceded from and waged war against the United States. They were defeated. On what terms, how and when should they be readmitted to the Union?

Moderate Republicans favoured a quick reconciliation. Though Lincoln himself had a personal aversion to slavery, his principal interest as president was not ensuring equal rights for all Americans; it was winning the civil war and keeping the United States together. As he wrote to Horace Greeley, a publisher, in 1862, “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it…What I do about slavery, and the coloured race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union.”

Many abolitionists—among them Frederick Douglass, born enslaved in Maryland and by the 1860s one of America’s most celebrated authors and orators—recognised this position as untenable. To Douglass, “the very stomach of this rebellion is the Negro in the condition of a slave.” He wanted enslaved Americans not just freed, but armed and trained to fight for the Union.

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

But Lincoln came to emancipation slowly, led by events more than principle. The border states (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri and West Virginia after its creation in 1863) declined his entreaties for gradual emancipation backed by compensation to slave owners. His push to send African-Americans to Liberia, the Caribbean or Central America found few takers.

As the war progressed, the Union’s need for soldiers grew. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation not only freed the enslaved, it also welcomed them into the army. Abolitionists recruited free African-Americans in the North, and in the South the Union’s fighting forces included the formerly enslaved. According to Eric Foner, a historian, by the war’s end 180,000 African-Americans had served in the Union Army.

Emancipation also bound the Union’s success to slavery’s demise. It seems obvious today that the two were always linked. After all, Alexander Stephens, the Confederacy’s vice-president, called slavery the “natural and normal condition” of “the Negro,” who “is not equal to the white man”. But, as Lincoln’s vacillation demonstrates, it was then not so clear, and many hoped for some sort of political reconciliation between northern and southern states under which slavery would somehow naturally die out.

Almost a year after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, Lincoln released his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction. This moderate plan promised readmission to Confederate states once 10% of their voters accepted abolition and swore loyalty to the Union. Once readmitted, states could draft new constitutions, form new governments and send federal representatives to Washington, dc.

The radical wing of Lincoln’s party abhorred the plan. Wendell Phillips, an abolitionist, said that it “frees the slave and ignores the Negro”, meaning that it made no provisions to aid the formerly enslaved, and said nothing about suffrage. But the border states also bristled; as Mr Foner notes, some Marylanders “felt compelled to deny that voting for abolition implied ‘any sympathy with Negro equality’”. This was not unusual; for many, abolition did not entail a belief in actual racial equality, just opposition to slavery.

Radical Republicans hoped that Andrew Johnson, who ascended to the presidency after Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, would hew more closely to their view that Reconstruction required more than just emancipation. They were disappointed. Johnson, a Democrat whom Lincoln made his running-mate on a unity ticket, disliked “slaveocracy”. He was also a bigot and a poor politician, and led his party to defeat in the elections of 1866 and 1867.

Though Radicals never made up a congressional majority, they held strong convictions and voted together while others wavered. They demanded full civil rights for freedmen, which few moderate Republicans did, and opposed compensating slaveholders. They also opposed any accommodation to slavery, such as the measures that would have preserved the Union at the cost of allowing slavery in newly admitted states.

After the 1867 elections, with Johnson weakened and Republicans holding a congressional majority, the Radicals’ solidarity put them in charge of Reconstruction policy. The most prominent among them was Thaddeus Stevens, a congressman from Pennsylvania. He saw the former Confederacy as conquered territory and believed “the whole fabric of southern society must be changed, and never can it be done if this opportunity is lost.” The Radicals divided the South into five military districts. They required the states to write new constitutions; ratify the 14th amendment, which granted citizenship to anyone born on American soil or naturalised in the United States; and allow black men to vote.

In the South, black political mobilisation was already under way, having begun before the war’s end. During Reconstruction, black electoral turnout often approached 90%. Former Confederate states elected over 2,000 black state and local officials and 185 black federal elected officials, including two senators from Mississippi (Hiram Revels and Blanche Bruce) and 14 members of Congress, with the largest number coming from South Carolina. Louisiana’s first and still only black governor, P.B.S. Pinchback, took office in 1872.

African-Americans in the South did not only vote for and seek office. Alongside white Republicans, they also rewrote their state constitutions, which as well as doing away with racially discriminatory laws also expanded state responsibility and civil liberties. Some established the South’s first state-funded schools and made attendance compulsory. Others opened state-run orphanages and asylums, reduced the number of crimes punishable by death, recognised a wife’s property rights independent of her husband and, in one state, authorised divorce.

The constitutional conventions and sizeable number of black elected officials were the fruits of rising black political mobilisation. Much like the civil-rights activists of the mid-20th century, they advocated for equal rights, and called on America to live up to its stated ideals. As one Alabama convention proclaimed, “We claim exactly the same rights, privileges and immunities as are enjoyed by white men…The law no longer knows white nor black, but simply men.”

Pastoral scene of the gallant South

Northerners, both black and white, came south to organise, teach and help. Many of the newly emancipated joined branches of the Union League, a Republican-affiliated organisation. Others formed and joined organisations of their own. They built schools and churches, and advocated for land reform. As W.E.B. Du Bois, a sociologist and civil-rights activist, noted in his magisterial “Black Reconstruction in America”, “Black folk wanted two things—first, land which they could own and work for their own crops…In addition to that, they wanted to know…They were consumed with curiosity at the meaning of the world.”

Freedmen’s desire for land made sense. They and their families had cleared and worked it without recompense, giving them a moral claim, and there was plenty of it. Much of the South was sparsely populated, and the war left many planters devastated and without the free labour that built their wealth. Mississippi and Louisiana auctioned off land in small parcels. But most states did little.

The new constitutions did not resolve every question that they raised. Most took no position on whether state-run schools should be integrated, though in every state, African-Americans opposed separating black and white pupils into different schools. Some used racially neutral language to facilitate discrimination. Georgia required jurors to be “worthy and intelligent”—subjective terms that permitted local officials to bar African-Americans from juries. This pattern—broad agreement on principles, but backsliding over implementation—was a hint of the problems to come.

Recalcitrant white Southerners also fought against Reconstruction in three main ways. First, they aligned with moderate Republicans, who were less insistent on sweeping social changes than the Radicals. This cleaved southern Republicans in two camps, leaving the Radicals isolated, and brought Democrat-backed moderates into power across much of the South in the 1860s. And then, in the aftermath of the war, southern legislatures passed an array of “Black Codes” that curtailed freedom for the newly emancipated. These codes authorised arrest and forced labour for pseudo-crimes such as “vagrancy” and “malicious mischief”.

Mississippi required African-Americans to hold written proof of employment for the year. Any worker who left his employer before year’s end would forfeit wages and be subject to arrest. South Carolina barred African-Americans from any job other than farmer or servant unless they paid a “tax” of up to $100 (over $1,600 today). In both cases these Black Codes did not take effect—the robust federal presence imposed by the Radicals and protests from Congress prevented it. But they indicated the depth of southern white opposition to racial equality, presaging the practices that came to be known as “Jim Crow” laws.

White Southerners also embarked on a campaign of racist terrorism, led by groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. Nowhere in the South did African-Americans escape terror’s shadow. The terrorists were not, as legend maintained for decades, poor, uneducated whites, but as a newspaper editor from North Carolina remarked, “men of property [and] respectable citizens”. State and local governments did little to stop the violence, which made them look weak and ineffective—a shared goal of the terrorists and the Democrats.

The elections of 1872 returned Republicans to power in the White House and across much of the South. But Radical power was waning. Soon after winning re-election, President Ulysses Grant’s support for their policies grew tepid. In the next presidential election, Reconstruction was not part of Republicans’ platform; their candidate, Rutherford Hayes, promised to restore “honest and capable local self-government” to the South if elected. The threat of terrorism left many southern Republicans, as one from Mississippi complained, feeling “helpless and unable to organise”.

Hayes’s opponent was Samuel Tilden, the Democratic governor of New York, who like Hayes was not terribly popular. The election’s results were disputed, marred by widespread violence and accusations of corruption. While Congress set up a commission to settle the dispute, Hayes’s moderate Republican allies began negotiations with Southern Democrats. The two sides struck a bargain, the terms of which remain unknown, but which resulted in Hayes’s inauguration, and an end to federal support for Reconstruction. This left the South, as a black Louisianan noted, in “the hands of the very men that held us as slaves”.

Here is a strange and bitter crop

Many black Southerners feared that “Redemption”, as whites called the end of Reconstruction, would lead to their re-enslavement. The 13th amendment, which outlawed slavery, prevented that—but only just. Men convicted of the flimsiest of crimes were leased to agricultural and industrial projects and forced to work without pay. Debt peonage kept rural African-American families bound to planters and merchants.

The 15th amendment barred explicitly denying black people the right to vote. Yet literacy requirements or poll taxes were often imposed in a racist way. An African-American could be deemed unfit to vote, for instance, if he failed to tell a white county clerk how many bubbles were in a bar of soap. When such tests failed, whites could always resort to violence without fear of conviction by all-white juries. By the mid-20th century, just 7% of Mississippi’s black adult population was registered to vote.

Denial of the franchise led to a decline in the number of black officials. By the turn of the 20th century, Congress had just one black member: George Henry White of North Carolina, who left office in 1901 after his state, like the rest of the South, enacted laws restricting black suffrage. After Blanche Bruce of Mississippi left office in 1881, 86 years would pass before the next African-American—Edward Brooke of Massachusetts—served in the Senate. Not until 2013 would two elected African-Americans (Tim Scott of South Carolina and Cory Booker of New Jersey) serve in the Senate together. After John Lynch lost in 1882, it took almost a century for Mississippi, America’s blackest state by share of population, to elect another black congressman, Mike Espy. After P.B.S. Pinchback left office in 1873, America would not see another black governor until 1990 when Virginians elected Douglas Wilder.

For years, the prevailing historical interpretation of Reconstruction—known as the Dunning School, after William Dunning, a professor who propounded it in the early 20th century—argued that it failed because black Southerners, in his words, “exercised an influence in political affairs out of all relation to their intelligence”. In this view, slavery was not an inexcusable evil and a betrayal of America’s founding ideals, but “a modus vivendi through which social life was possible…[between] two races so distinct in their characteristics as to render coalescence impossible.”

By placing the blame for Reconstruction’s failure on African-Americans, the Dunning School justified Jim Crow and legal segregation. It also undergirded the “Lost Cause” mythology propounded by the defeated South, which argued that it waged a defensive struggle against a tyrannical invader rather than an offensive war (the South fired the civil war’s first shot) for the right to enslave others. Part of the cost of reconciliation was that in the decades immediately following Reconstruction’s end, the civil war came to be seen as a battle between equally brave soldiers now at peace with each other, rather than, as Douglass wrote, “a contest of civilisation against barbarism”.

Du Bois’s study of Reconstruction, published in 1935, took aim at the Dunning School. Du Bois argued that Republicans and black Southerners laid the groundwork for a new and more activist conception of the state. They were the principal agents, politically and intellectually, of their own liberation. It was not their corruption or unpreparedness that condemned Reconstruction; it was implacable white opposition to democracy and devotion to racist rule backed by violence. That view, built upon by Mr Foner and others, now predominates.

Even so, some of the battle lines drawn by Reconstruction remain. President Donald Trump’s exploitation of white racial grievance echoes that of the Redeemers, as does his fondness for Confederate iconography. Some on the right, including Mr Trump, oppose birthright citizenship. Revanchist white Southerners spent a century keeping African-Americans from voting, in defiance of the 15th amendment; as recently as 2013, Republicans in North Carolina tried to pass a voter id law that “target[ed] African-Americans with almost surgical precision”, in the words of the judge who struck it down.

Although Reconstruction was a failure, it shaped the country in positive ways. After the civil war ended, the newly emancipated formed their own political organisations and churches—the latter of which would come to play a central role in the civil-rights movement of the mid-20th century and beyond. States such as Georgia, which had no state-funded school system before Reconstruction, would retain it after Redemption, though not until 1954 would the Supreme Court bar racial segregation in schools. The 14th amendment’s Equal Protection Clause—which forbids “any State [from denying] to any person within its jurisdiction equal protection of the laws”—has been used to abolish segregated schools, anti-miscegenation rules and other racist laws.

Still, anyone who believes in American ideals will find it difficult to ponder Reconstruction’s unfulfilled promise without grief and anger. The lament with which Du Bois ends his masterpiece remains sadly true today: “If the Reconstruction of the Southern states, from slavery to free labour, from aristocracy to industrial democracy, had been conceived as a major national programme of America, whose accomplishment at any price was well worth the effort, we should be living today in a different world.”

By The Economist