But the real damage from Brexit will take time to make itself felt

FOR THE four-and-a-half years since Britain’s referendum on membership of the European Union, firms have been worrying about the impact of Brexit. But Britain’s transition out of the EU, completed on December 31st, did not end with a bang. The queues of lorries at Dover that had been widely predicted failed to materialise. Supermarket shoppers were not starved of green vegetables. And business has had other troubles on its mind.

England’s third national lockdown began on January 6th. Non-essential retail and much of the hospitality sector are once again shut. The government has taken steps to soften the blow. Rishi Sunak, the chancellor of the exchequer, announced a further £4.6bn ($6.2bn) package of grants, worth around 0.2% of pre-crisis GDP, for firms as the lockdown began and signalled that more support may be forthcoming at his next budget, due in early March. The job-retention scheme, under which the state will pay up to 80% of the wages of furloughed employees, has already been extended until the end of April and the Treasury has not ruled out a further continuation. With many firms now better adapted to home working, more retailers offering an online service and more restaurants better set up to handle takeaway business, GDP should not shrink as fast as it did in April 2020 (see chart).

Still, the immediate prospects are grim. Schools have been closed, as they were in the first but not the second lockdown, so many parents are unable to work. Samuel Tombs of Pantheon Macroeconomics, a consultancy, reckons that the impact of the third lockdown will be closer to that of the first than the second.

Although the resurgence of covid-19 has overshadowed Brexit so far this year, the latter is causing some difficulties. The hassle of new VAT arrangements has prompted many global smaller businesses to halt shipments to Britain entirely. Dutch Bike Bits, an online retailer of bicycle parts, has described the new British arrangements as “ludicrous” and halted sales to Britain in December. Traffic ran smoothly on the crucial Dover-Calais route in the first week of the new arrangements but stockpiling before they were introduced may have eased the transition. The government has warned hauliers that delays are likely as volumes increase and enforcement of the new rules becomes tighter.

Disruption has already been more evident in Northern Ireland. To avoid creating a hard border on the island of Ireland, Britain and the EU agreed that there should be a new internal border in the United Kingdom, between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Freight businesses worry that importers have not fully grasped how the system is supposed to function. The complexity of the customs procedures has led some firms to give up trading or narrow product ranges. Marks and Spencer, a retailer, has temporarily dropped several hundred products in its 21 Northern Irish stores, ranging from BrewDog beer to bin bags.

But the real hit to Britain’s economy from Brexit is likely to come as a whimper rather than a bang. By doing a last-minute trade deal, Britain and the EU avoided short-term disruption, but economists worry more about the return of the “British disease” of the post-war years—hence the Bank of England’s prediction that the British economy will be three or four percentage points smaller in ten years’ time than it would be had it stayed in the European single market and customs union.

In the three decades after the second world war, Britain’s economy declined relative to its European neighbours. That was not just because Germany and France had so much ground to make up after the war; by the 1960s, they were beginning to pull ahead. Britain suffered from what was known at the time as the “British disease”: confrontational industrial relations, poor management, weak productivity and low investment.

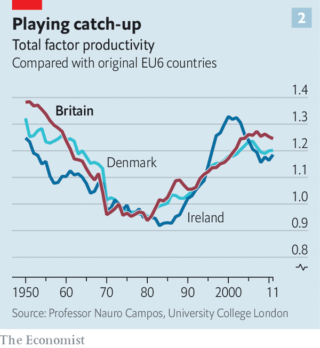

Margaret Thatcher is often credited with changing the country’s trajectory, but many economists argue that Britain’s entry to the then European Economic Community (EEC—now the EU) in 1973 was at least as important. Nauro Campos and Fabrizio Coricelli of the Centre for Economic Policy Research, a network of economists, point to a similar productivity-growth pattern among the three countries—Britain, Denmark and Ireland—that joined the EEC in 1973 (see chart). Mr Campos thinks that Britain’s entry into the common market created the conditions for Thatcherism to thrive by offering British entrepreneurs access to a larger, deeper and more innovative market than they had previously ever thought possible.

Nicholas Crafts, a leading historian of Britain’s economy, argues that the real cause of the British disease was a lack of competition in the domestic economy, which was widely cartelised in the interwar years and sheltered from international competition in the post-war decades. Thatcher, by his reckoning, deserves credit for liberalising markets and deregulating industries but was aided by the wider exposure of firms to international competitive pressure from entry into the EEC and the creation of the European Single Market in the mid-1980s. He reckons that Britain’s failure to join the EEC at its creation in 1957 had a substantial cost in terms of lost productivity.

If the effect of leaving the EU is the opposite of joining it, the impact will not be a swift, painful recession, it will be growth forgone. Britain will be like a boiled frog, not noticing the damage until it is done.

By The Economist

ogh! Hope Æ´ou get the issue fixed soon. Thanks

I have no doubt that this is clear enough.

Wow, this is a cool article and great look and feel as well.

Fairly insightful publish. Never believed that it was this simple after all. I had spent a great deal of my time looking for someone to explain this topic clearly and you’re the only one that ever did that. Kudos to you! Keep it up

Pretty fine post. I just stumbled upon your site and wanted to say that I have in reality enjoyed reading your website posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you post again soon.