From Jack Ma to extraterritorial laws, the government is throwing its weight around

HONG KONG – WHEN AMERICA slammed sanctions on Huawei, barring American firms from supplying the Chinese telecoms-equipment titan on national-security grounds, China’s state media predicted that the restrictions would spur innovation in the local technology industry. In time, they may well do. But for now, much of the innovating is taking place within the Chinese state as it experiments with a new system of control over Chinese business.

On January 9th the Ministry of Commerce struck back against American sanctions. It said that it may force Chinese companies to stop complying with “unjustified extra-territorial application of foreign legislation” (in Beijing’s eyes, that means virtually all of it). It also gave Chinese firms the right to sue foreign and domestic companies that have complied with some foreign sanctions for compensation.

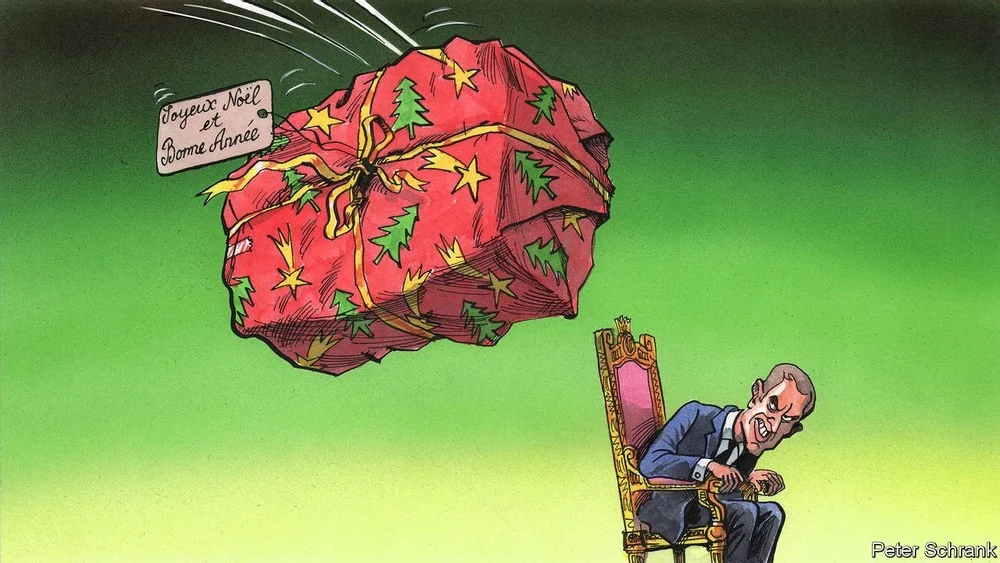

The measures are part of a broader trend, as the Communist regime led by Xi Jinping adopts an increasingly muscular stance towards the private sector. In November it halted the $37bn initial public offering of Ant Group, the payments affiliate of Alibaba, China’s biggest e-commerce empire, two days before the firm was due to debut in Shanghai and Hong Kong. The same month the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), created in 2018 from three regulators, issued rules to rein in e-commerce giants and, in December, it opened an antitrust investigation into Alibaba. On January 10th the Communist Party’s main body for political and legal affairs vowed to take trust-busting more seriously.

The antitrust buildup has spooked investors—Alibaba’s share price has dropped by a quarter since October. And the barrage of new rules creates uncertainty for business in two other ways. First, who is in charge of one of the world’s biggest companies. Jack Ma, the tycoon who co-founded both Alibaba and Ant, has not been seen in public since October, when he likened Chinese state banks to pawn shops. He owns just 4.8% of Alibaba and stepped down as chairman in 2019, but is thought to remain firmly in control of strategic decisions. Even if he does resurface soon, as other AWOL tycoons have in the past, after showing contrition and “assisting” investigators, the episode sends a chilling signal.

The blowback could yet destabilise Alibaba in unexpected ways. Like many mainland tech firms, it uses an offshore legal structure that allows foreigners to invest in Chinese assets that would otherwise be off limits. The arrangement has been tolerated by regulators, without being fully endorsed by them, for two decades. But last month SAMR fined Alibaba and Tencent, another internet behemoth, for not seeking approvals for past acquisitions. If the firm is subject to a sustained legal onslaught by regulators it could raise doubts about the sustainability of these complex foreign-ownership arrangements—a situation that would further spook outside investors in tech groups in China.

The other immediate source of instability is the battle between the superpowers over their extraterritorial legal reach. In 2019 the commerce ministry dabbled with this by creating a list of “unreliable entities”. So far it has not been populated with any prominent foreign companies. Rumours that it would include HSBC, a British bank that played a role in an American investigation into Huawei, turned out to be wrong. If the commerce ministry acts more decisively this time, its proposed measures could pose an impossible dilemma for Western multinationals in China: either face fines in America for breaking sanctions, or end up in a Chinese court. Wang Jiangyu of the City University of Hong Kong imagines that the new rules will force global businesses to do something they would love to avoid: take sides.

The measures are a mixed blessing even for Chinese firms, which they are ostensibly designed to assist. Many firms could, it is true, seek damages from foreign partners. But some Chinese firms may be damaged themselves—for instance, mainland banks operating abroad which have abided by Uncle Sam’s sanctions over the years in order to avoid fines and maintain access to the dollar-clearing system, the backbone of global finance. Chinese lenders that have been forced to shut Hong Kong accounts for blacklisted Chinese companies and individuals could come under fire. Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s leader, who has overseen a crackdown on pro-democracy activists, has said she has cash piling up in her apartment, unable to deposit it in a bank as a result of American sanctions against her.

In the short run, concludes a trade lawyer in Washington, DC, the commerce ministry’s rules are “more likely to sow discord than actually help Chinese companies”. This is not exactly conducive to innovation. Nor is the long arm of the Chinese state, especially as it grows ever longer and beefier.

By The Economist

Im wondering if you have noticed how the media has changed? Now it seems that it is discussed thoroughly and more in depth. Overall though Im looking for a change.

When I view your RSS feed it gives me a bunch of strange characters, is the issue on my reader?

I completely agree with the above comment, the internet is with a doubt growing into the a excellent number of important medium of communication across the globe and its due to sites like this that ideas are spreading so quickly. My best wishes, Alda.

I was just chatting with my coworker about this today at Outback steak house. Don’t remember how in the world we landed on the topic in truth, they brought it up. I do recall eating a outstanding fruit salad with cranberries on it. I digress

Lately, I did not give a lot of consideration to giving comments on site page posts and have placed feedback even much less. Reading through your pleasant post, will support me to do so sometimes.