Stockmarkets are pricing in an economic snap-back and growth on top of it. That may be too rosy

NEW YORK – BEFORE THE pandemic investors favoured companies with strong sales growth, low debt and high return on assets. In the past three months, they have been ploughing money into smaller, underperforming firms that have barely survived the covid-19 recession. A robust economic recovery, Wall Street seems to think, will pull the most covid-impaired away from the abyss and towards financial outperformance. Right now, says Jonathan Golub of Credit Suisse, an investment bank, “the market is rewarding failure.”

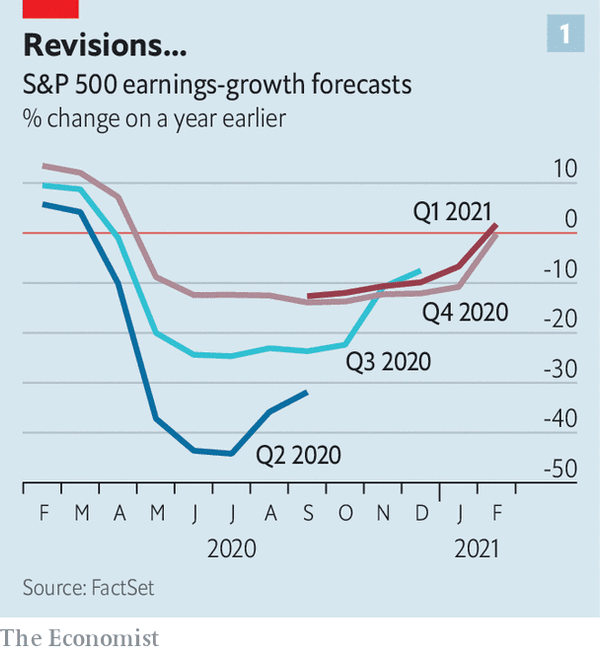

The bet on weaklings is the latest sign, if any more were needed, that 2020 marked a weird year in modern corporate history. Far from imploding, as many feared after the virus drained the life out of the world’s stockmarkets in March, America Inc has emerged from the plague year looking astonishingly healthy. It did not take long for analysts to start revising their profit forecasts back up (see chart 1). Even then, four in five of those big firms which have reported their latest quarterly results beat projections. Their aggregate earnings in the three months to December surpassed estimates by over 17%.

The losers—particularly in industries such as hospitality, travel and energy, which rely on people mixing or moving about—lost a lot. Of the 305 S&P 500 firms that have so far presented full-year results, 42 ended 2020 in the red, up from 18 the year before. Their losses added up to $177bn, five times as much as the comparable figure in 2019. But the winners won big: $860bn, all told, just 12% below last year’s profit pool. The technology titans without whose products socially distant shopping, work, socialising and entertainment would be impossible made more money than ever. Wall Street appears to be wagering that both winners and losers have room for improvement (see chart 2).

Big firms are the most bullish. A survey last month by Corporate Board Member, a trade publication, found that overall confidence has risen at public companies. Nearly two in three board members rated their firm’s outlook “very good” or “excellent”. Three-quarters of chief executives expect revenues and profits to increase, compared with less than two-thirds in December. Half predict increased investment.

Lacking the access to capital enjoyed by bigger firms, most of the smaller firms of the Russell 2000 index were bleeding red ink mid-pandemic. Now things are looking up even for them. In the last quarter the Russell 2000 posted a gain of 31% , far outpacing the 12% notched up by the S&P 500. The latest survey by Vistage, an executive-coaching outfit, found that 64% of bosses at small and medium-sized business plan to expand their workforce this year, up by a fifth from the previous quarter. Two-thirds think sales will increase in 2021. Over half expect profitability to rise.

There are two main reasons for this perkiness. First, investors are pricing in the successful rollout of vaccines in America by the summer, which would help reopen the economy. Citigroup, a bank, calculates that Americans have squirrelled away nearly $1.4trn in unspent income over the past year, which translates into oodles of pent-up demand. All told, $5trn or so is sitting idle in money-market funds which could be spent—on everything from a fresh pair of shoes to new shares—once the pandemic recedes. Second, it is widely assumed that unified Democratic control of the White House and Congress will mean continued fiscal and monetary stimulus that could fuel that demand further still.

These considerations have led financial forecasters to project that S&P 500 revenues in 2021 will match or surpass the levels seen in pre-pandemic 2019 for most sectors, according to Goldman Sachs, an investment bank. By 2022 everyone except America’s oilmen should be in rude health. Gregg Lemos-Stein of S&P Global, a credit-rating agency, foresees a speedier-than-expected revival in health care, building materials, business services and non-essential retail (see chart 3). On this interpretation, share prices have room to soar.

Two dangers lurk. If President Joe Biden fails to get something resembling his proposed $1.9trn stimulus through Congress, investors and bosses may start feeling jittery, regardless of the views of macroeconomists, many of whom worry that the stimulus plan is excessive. Given the uncertainty over post-pandemic demand for large industries such as corporate air travel, now that CEOs have concluded that Zoom is often a decent alternative, understimulation is a bigger risk than overstimulation, says the boss of a big private-equity firm.

The other danger is the vaccine rollout. The pace at which American states are administering the inoculations is indeed decent compared with most other big countries; only Britain has done a better job so far. But nine in ten Americans have yet to receive a single dose, let alone the full two. And a distressingly large share may refuse to be vaccinated. At the same time, the emergence of virulent new strains of the virus could mean that the transition from pandemic to no pandemic will not be a binary switch but a sliding scale. American business may need to cope with a much messier scenario of partial lockdowns and ongoing endemic disease for years.

In 2020 a strong stockmarket sat awkwardly atop a sickly economy. In 2021 the opposite may be true, thinks Michael Wilson, of Morgan Stanley, a bank. Yes, the recovery will be “extraordinarily robust”, he believes, with both GDP and earnings growing briskly. But, he warns, the stockmarket has “already priced in too much good news”. The pandemic year’s corporate champions may find that their solid sales included a lot that were pulled forward, so disappointment is all too conceivable. The stragglers’ valuations already look rich.

If the virus does turn endemic, and the recovery slows, the disconnect between Wall Street and Main Street may become untenable. Tobias Levkovich of Citigroup is confident that companies will learn how to find opportunities even under conditions of continued topsy-turviness. As for investors, the best ones “don’t try to predict the market,” says the private-equity boss. “They adapt quickly.” The year 2021 will offer them plenty of opportunities to shine in that department.

By The Economist