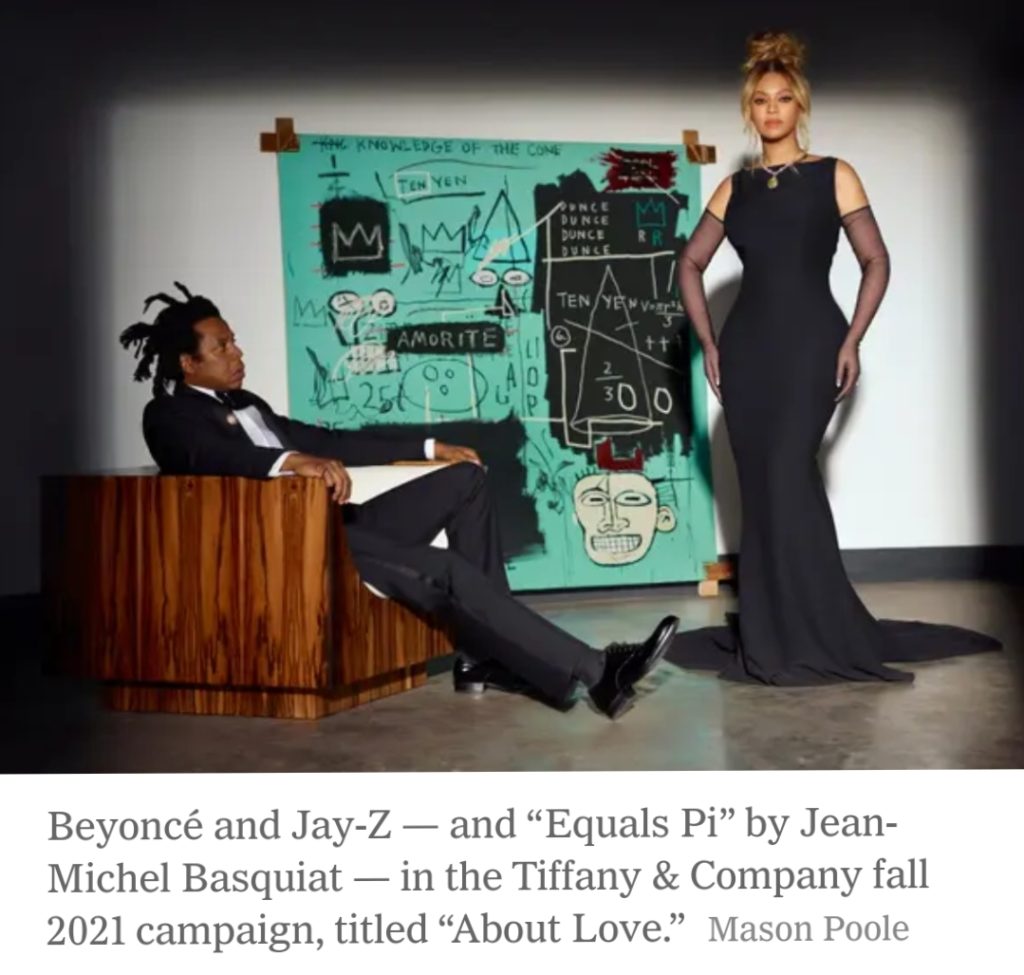

Last week, when the new Tiffany & Company ad campaign broke featuring the quartet of Beyoncé, Jay-Z, a 128-carat diamond and a rarely seen Jean-Michel Basquiat painting that had recently been acquired by the jewelry brand’s new owner, LVMH — all in a sort of contemporary remake of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” — it set off a social media storm involving a multiplicity of debates.

Some loved it, some did not. Some were upset about the question of art versus commerce (or art being used to market commerce); others about the racist history of diamond mining.

But one of the odder brouhahas centered around the color of the painting, “Equals Pi,” thanks to a comment by Alexandre Arnault, Tiffany’s new executive vice president of product and communications, in an interview with WWD about the campaign. He suggested, almost as an aside, that perhaps the shade of blue used as the painting’s background was, in fact, an “homage” to Tiffany and its signature color, generally referred to as robin’s egg blue.

Specifically, WWD reported that he said: “We don’t have any literature that says he made the painting for Tiffany. But we know a little bit about Basquiat. We know his family. We did an exhibition of his work at the Louis Vuitton Foundation a few years back. We know he loved New York, and that he loved luxury and he loved jewelry. My guess is that the [blue painting] is not by chance. The color is so specific that it has to be some kind of homage.”

According to a Tiffany spokeswoman, this was not a joke — and indeed, some seem to have taken it as a challenge: to the integrity of art, and the artist. Basquiat died in 1988 at 27, but in the last few days all sorts of people with various relationships to both him and his work have come out with their own theories on the painting’s origin story.

It started with a man called Stephen Torton, who identified himself as a former assistant of Basquiat’s and posted an Instagram statement saying, “I designed and built stretchers, painted backgrounds, glued drawings down on canvas, chauffeured, traveled extensively, spoke freely about many topics and worked endless hours side by side in silence. The idea that this blue background, which I mixed and applied was in any way related to Tiffany Blue is so absurd that at first I chose not to comment. But this very perverse appropriation of the artist’s inspiration is too much.”

The controversy has even drawn out the first owner of the painting. Anne Dayton was advertising director of the magazine Artforum when she went to a show at the Fun Gallery on East 10th Street in 1982 and the gallery’s owner, Patti Astor, showed her the painting, then called “Still Pi,” Ms. Dayton recently told The New York Times. She bought it for $7,000 (she still has the bill of sale).

Tiffany never came up in the discussions around what was so exciting about the painting, she said.

“At no moment whatsoever was there any connection between ‘Equal Pi’ and Tiffany’s blue box,” she wrote in an email. “It is blasphemy to even consider it. Basquiat’s raw, visceral and subversive power was the antithesis of the traditional classicalism of the Tiffany standard.”

Indeed, she wrote, while fashion and the art were close at the time — the Artforum cover for February 1982 featured Issey Miyake — the designers that were part of the scene “were all breaking rules,” including Yohji Yamamoto, Comme des Garçons, Kenzo and Gianni Versace. “Tiffany’s was as far away from the scene as it could possibly be,” Ms. Dayton noted.

She sold “Still Pi” on May 3, 1989 at a Sotheby’s sale (in the New York Contemporary Art, Part II, catalog it was called “Equals,” though on Ms. Dayton’s receipt it is “Equals Pi”). It went for $200,000 to a phone bidder, and she said she “never saw the painting again until now.”

According to Larry Gagosian, the art dealer with whom Basquiat lived and worked in Los Angeles around 1982 and who represented the artist at that time, he had recently been made aware of what was going on (Mr. Gagosian has sold a fair amount of art to both the Arnault family and LVMH, but he said he was not involved with the sale of this painting).

Though he could not recall this painting and said he had never heard of Mr. Torton, Mr. Gagosian said on a phone call that Mr. Basquiat painted “well over 50” canvases when they were together and he used to watch the artist at work.

His take on the matter, he said, was that as far as he knew, Mr. Basquiat always mixed his own colors. But while the artist might well have been aware of Tiffany’s blue boxes — Mr. Basquiat “liked to shop,” said Mr. Gagosian, and was highly culturally attuned — suggesting the blue was a reference to a luxury brand was probably a leap of logic too far.

“It’s a very evocative color,” Mr. Gagosian said, noting it was used in other Basquait paintings. The artist “probably just liked it,” he said.

(The brand’s color, which Charles Lewis Tiffany began using in 1845, was not trademarked until 1998, when it became one of only a few shades to receive legal recognition; now it is the private custom Pantone Color No. 1837, a reference to the year Tiffany was founded.)

Mr. Arnault does seem to have — well, reframed his original thinking a bit. “The beauty of art is that it can be interpreted in a number of ways,” he said in a statement to The Times. “All important works provoke thought and create a dialogue. Jean-Michel Basquiat’s ‘Equals Pi’ is no different.”

Whether any of this will make a difference after the painting is hung in the Tiffany flagship on Fifth Avenue, its ultimate destination, is unclear. Once a painting, or any piece of art for that matter, is out in the world, it takes on a life of its own. Meaning, like love, is in the eye of the beholder. And for now, this marriage of art and commerce seems quite convenient.

By Vanessa Friedman/The New York Times