What would you rather have: an orgasm or a pastrami sandwich? The woman at the table next to Meg Ryan and Billy Crystal in Katz’s Delicatessen in “When Harry Met Sally” chose poorly. She plumped for the turkey sandwich that seemed to have inspired Sally’s simulated raptures. She should have picked what he was having: the pastrami.

Pastrami on rye is the platonic ideal of the New York deli sandwich. The version Harry demolished as Sally educated him in the ways of womankind was oddly modest. He was able to get his chops around it with little effort and no mess. A perfect pastrami sandwich should be large enough to inspire a certain apprehension. It is testimony to the Jewish fear that someone, somewhere might at some point go hungry.

Jews did not invent pastrami. In Ottoman Turkey, basturma or pastirma was a kind of pressed, spiced meat – beef, goat or mutton – not unlike jerky. It may have been produced by horse riders stashing the beef in their saddlebags and pressing it with their thighs as they rode. The recipe travelled along the spice route to Romania, where goose became the meat of choice.

The late 19th century and early 20th century saw a surge of Jewish immigrants to New York from across eastern Europe, including Romania. An earlier rush of German migrants to the east coast had brought a delectable range of smoked and cured meats and sausages. When Romanian Jews introduced the pastrami, they soon abandoned the traditional goose in favour of beef, which was cheaper and more readily available.

A pastrami sandwich is testimony to the Jewish fear that someone, somewhere might at some point go hungry

Some credit Sussman Volk, a Lithuanian butcher, with being the first to sell a pastrami sandwich in New York. In 1887 a Romanian friend asked Volk to mind his suitcase while he returned to Romania; in exchange, he gave Volk his recipe for pastrami. One customer asked for his meat on slices of rye bread and the pastrami sandwich – and the New York Jewish deli – were born. Inevitably this story is disputed (two Jews, three opinions). Others reckon Katz’s, which gives its founding date as 1888 (though others dispute this), was the first place to sell pastrami.

The pastrami sandwich soon spread far beyond the delis of New York. Established meat-producers, many of them German migrants, began making the stuff and shipping it around America, as well as farther afield.

But this trade may have inadvertently contributed to pastrami’s growing popularity in another, less appetising, way, says Robert Moss, an American food writer. In May 1897 Adolph Louis Luetgert, a well-known German sausage-maker in Chicago, was arrested for murdering his wife, Louisa. During a search of his factory, police found tiny pieces of bone and two gold rings, one a wedding band engraved with the letters L.L., in a sausage vat.

The story of the Sausage King who dissolved his wife in lye made headlines around America. Rumours inevitably spread that she had ended up in some of his products. The country’s appetite for sausages is thought by some historians to have diminished as a result. Customers shook their heads “darkly” at the mention of sausages, butchers as far as Kansas are reported as saying, and people instead turned to pastrami.

They were right to use butchers rather than make pastrami at home, which is a significant undertaking that requires time and, ideally, a smoker. Even the best get some help. Katz’s pastrami is smoked off-site.

Food and sex have always been closely linked in Jewish thinking

The favoured cut – the navel – is fatty, tough and cheap, ideal for the long cooking process. First comes the brine. Salting meat preserves it but also adds flavour and changes the texture, making it denser and easier to slice. Curing salt keeps the beef rosy pink beneath a crusty, spicy, black bark. The meat sits in the brine for a good five days before “the rub” with spices, which can include a number of flavours – most importantly the heat of black pepper and the nutty, citrussy freshness of coriander.

Then come several days of smoking, followed by the boil, until the meat is cooked through to a delicate wobble. A short steam just before the meat is sliced brings it to maximum tenderness before it’s loaded onto bread (Katz’s steamers are as “big as an office desk”).

The bread and trimmings are crucial, too. Pastrami comes on rye, ideally flecked with fragrant caraway seeds and smeared with brown mustard. On the side is a pickle, which can be “full sour” or a slightly fresher “half sour”. But the meat is the thing. Fat coats the tongue and lets the flavours linger. In the absence of other moistening components such as mayonnaise or tomatoes – clearly verboten – it also lubricates the meat.

The excesses of the pastrami sandwich are part of its pleasure. In his book, “Pastrami on Rye: An Overstuffed History of the Jewish Deli”, Ted Merwin points out that “the meat is crammed between the bread” in a way that “recalls the act of copulation”.

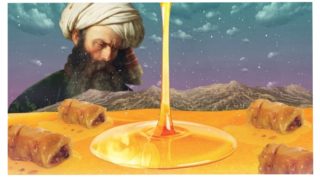

Food and sex have always been closely linked in Jewish thinking. Foods such as honey, pomegranates and figs are the more traditional aphrodisiacs. But pastrami has its own power. In one episode of “Seinfeld” George Costanza is overcome with lust when a date produces a platter of cured beef with the explanation: “I find the pastrami to be the most sensual of all the salted, cured meats.” You’ll never see a sandwich the same way again.

By Josie Delap, The Economist’s International editor and writes about food for 1843 magazine

ILLUSTRATIONS: ALBANE SIMON

THE ECONOMIST