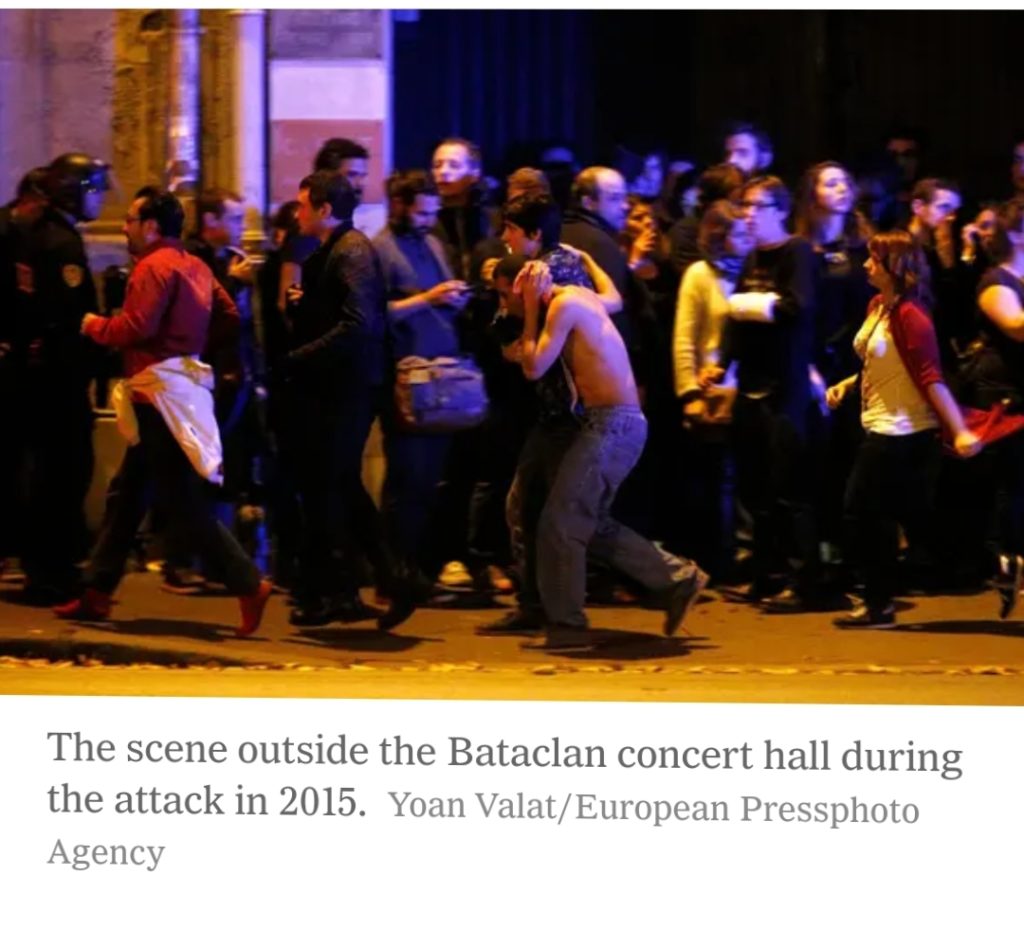

PARIS — Marilyn Garnier, a survivor of a terrorist attack at the Bataclan concert hall in Paris, can never forget that evening.

It was Nov. 13, 2015. Firecracker noises erupted at the back of the crowd. Her partner pushed her to the floor, where they lay still, overcome by the smell of blood and gunpowder. Bursts of gunfire punctuated a deathly silence.

“At that moment, you don’t think you are going to survive,” Ms. Garnier, now 30, recalled.

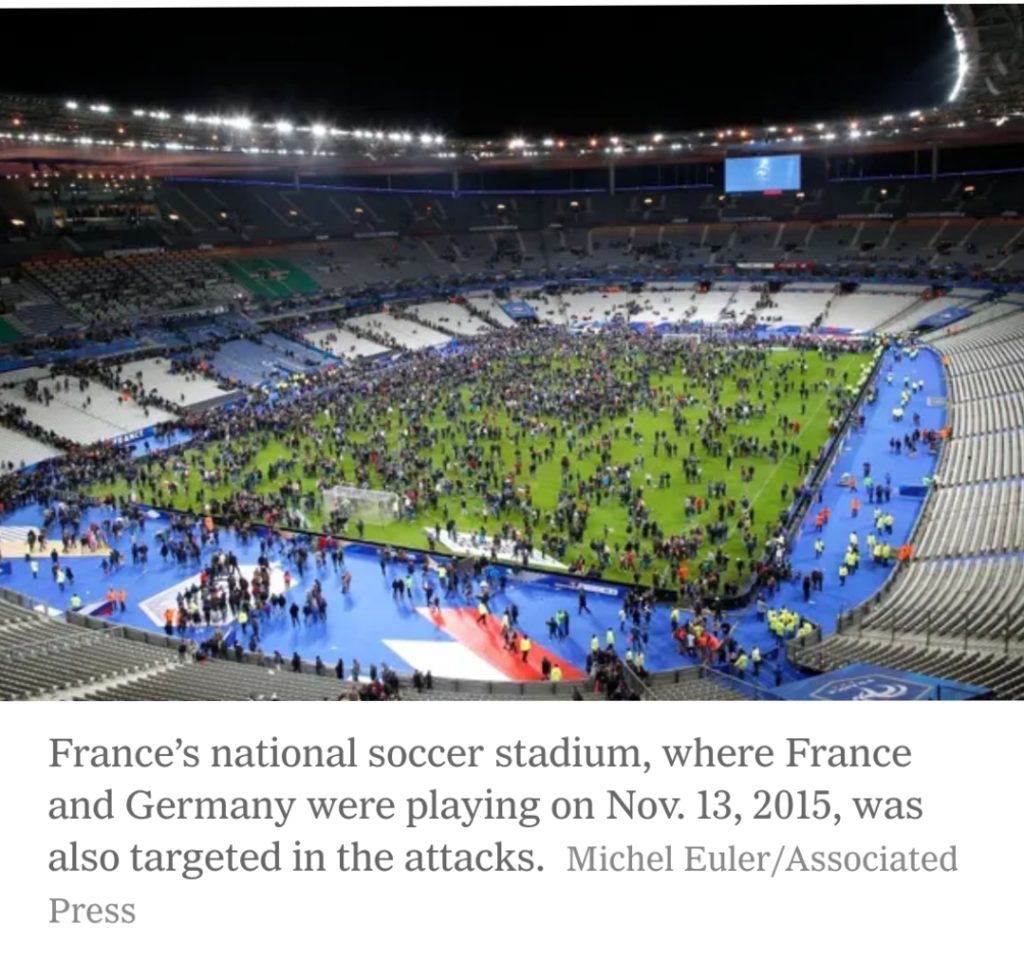

Nearly six years later, the historic trial of the those behind the 2015 attacks — which, besides the Bataclan, also targeted an area outside France’s national soccer stadium and the terraces of cafes and restaurants in central Paris — began on Wednesday in the French capital. It is expected to last a record nine months.

The coordinated assaults — a series of shootings and suicide bombings — were carried out by 10 Islamic State extremists who killed 130 people and wounded nearly 500 others, shaking France to its core. (One survivor who suffered from severe trauma and killed himself in 2017 was officially declared the 131st victim.)

Of the 10 attackers, nine were killed. Most carried out suicide bombings or were killed by the police, including in a shootout several days later when the authorities raided a hide-out north of Paris.

Twenty men will be tried by a panel of judges, including Salah Abdeslam, who prosecutors say is the sole surviving attacker, and others who are accused of helping to plan and coordinate the assaults.

When Mr. Abdeslam, who arrived at the courthouse on Wednesday under tight police escort, was asked by the presiding judge to confirm his name, he started by invoking God.

“I abandoned all professions to become a fighter for the Islamic State,” Mr. Abdeslam, wearing a black T-shirt and black face mask, said when asked about his job.

Over 300 lawyers and nearly 1,800 plaintiffs will take part in the trial. People can become a “partie civile,” or plaintiff, in a French criminal trial if they were harmed by the crime in question, a status that could give them the right to compensation.

A courtroom with space for 550 people was built specifically for the monumental proceedings, which will be the first to be accessible for plaintiffs on a live internet radio. It will also be one of the rare trials in France to be filmed.

“It’s the trial of all superlatives,” Éric Dupond-Moretti, the French justice minister, said this week at the courthouse on the Île de la Cité, an island on the Seine River that will be partly locked down by the police for the duration of the trial. “The longest trial in our history,” he added.

On Wednesday, the courthouse, surrounded by checkpoints, was teeming with camera-toting journalists and police officers with bomb-sniffing dogs. Plaintiffs were offered lanyards indicating their willingness to talk to the news media — green for yes, red for no.

While the November 2015 attacks saw France unite in mourning, it also instilled deep fears. The attacks came months after deadly shootings at a kosher supermarket and at the offices of Charlie Hebdo, a satirical newspaper, and deepened wounds in French society that have yet to fully heal. Unresolved debates continue over the place of Islam in France, immigration, and the balance between security and civil liberties.

François Hollande, the socialist president of France at the time of the attacks, has told Le Parisien that his time in office, “whether I like it or not, bears the traces of what happened that Nov. 13, and, more generally, of Islamist terrorism.”

“Each time a new terrorist attack occurs, it plunges me back into that dark night,” said Mr. Hollande, who will testify at the trial, a first for a former president.

For some survivors, a door slamming or a car backfiring may be all it takes.

Ms. Garnier escaped from the Bataclan uninjured after bursting through an emergency exit. But she wants to see the accused in person and wants the world to understand what victims have been through: the exhausting hyper-vigilance, the endless medical procedures, the administrative obstacle course to get compensation from France’s official victim’s fund, the isolation from friends and family, the broken careers.

“To measure the real impact that this event had on our lives,” Ms. Garnier said. “So that they really realize that six years later, it’s still very, very close.”

Stéphanie Zarev, 48, who was also in the Bataclan that night, said that for years she was plagued by panic attacks and flashbacks. She has avoided watching or reading about the attacks.

“But now,” she said, “I need to know.”

She hopes that the testimonies will help her understand how the attacks came to be. Her fear is that the trial, delayed by the coronavirus pandemic and coinciding with France’s 2022 presidential election, will be used to score political points.

While France has avoided a mass casualty attack since a 2016 truck massacre in Nice, a string of smaller-scale stabbings and shootings have kept terrorism fears particularly acute.

“In France, there was a before and after Nov. 13, 2015, just like in the United States there was a before and after Sept. 11,” said Georges Fenech, a former lawmaker who led a parliamentary inquiry into the 2015 attacks that found failings by French security services.

In both cases, “we were the victims of new forms of terrorist threats that were previously unknown, and that challenged all of our strategies,” he said, acknowledging that France, which has passed a raft of antiterrorism and anti-extremism bills in recent years, had put in place many of the inquiry’s recommendations.

The Nov. 13 assailants were mostly French citizens who, in a carefully orchestrated plot, had traveled to ISIS-controlled territory in Syria for military training, before returning to Europe, where the attacks were prepared, mainly in Belgium.

The men accused in the trial, who are mostly in their 20s and 30s, face a range of charges, including complicity with murder and hostage-taking — the Bataclan attackers held hostages in the concert hall for several hours — as well as organizing a terrorist conspiracy. Most face sentences ranging from 20 years to life in prison.

Prosecutors say many of the accused men helped the Nov. 13 attackers by renting hide-outs to stash weapons and explosives, driving members of the cell across borders or securing cash and fake documents. Fourteen will attend the trial in person after being arrested mainly in France and Belgium, while six others who are still wanted for arrest will be tried in absentia.

Several are presumed to have been killed by Western airstrikes against territory that ISIS used to control in Iraq and Syria — including Oussama Atar, a Belgian-Moroccan who investigators suspect of planning the attacks, and Fabien and Jean-Michel Clain, two French jihadists who recorded the group’s claim of responsibility for the killings.

Only Mr. Abdeslam stands directly accused of murder, attempted murder and hostage-taking.

Mr. Abdeslam, a French citizen of Moroccan ancestry who lived in Belgium, played a key role in the attack, prosecutors say, but did not detonate his explosive vest. Investigators believe that it malfunctioned and that he fled in the hours that followed, prompting a monthslong manhunt.

Mr. Abdeslam has not cooperated with investigators. At a trial in 2018 in Belgium, where he was convicted of shooting at officers in Brussels while on the run, he barely said a word.

Still, plaintiffs like Fabienne Kirchheim, whose brother Jean-Jacques Kirchheim, 44, was killed at the Bataclan, hope that justice will be served.

“Through these attacks, the values of the Republic came under fire,” Ms. Kirchheim said. “Now I expect that same Republic to judge and punish, in a fair and democratic way, those attackers.”

Others have mixed feelings about the spotlight. Karena Garnier, another Bataclan survivor, was dreading the trial and had no intention of becoming a plaintiff.

The attention on the trial felt “like a huge invasion of privacy of this tragic event that happened to me,” said Ms. Garnier, 45, an American resident of France. But after talking with others in a victims’ group she belongs to, she said she changed her mind, even if the trial will not erase years of therapy, nerve-racking anxiety or bouts of work-disrupting brain fog.

“It’s really just to get some closure,” she said. “And to be there for my friends.”

By Aurelien Breeden/The New York Times