FOR MORE than 15 years, the “big three” of men’s tennis—Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic—have had a stranglehold of the game. They have won 60 of the past 73 grand-slams, the sport’s most important tournaments, winning 20 each. All three have enjoyed periods as the undisputed champion. But in recent years, as injuries and age have ravaged Messrs Nadal and Federer, Mr Djokovic has surged ahead. In 2021, he was imperious, winning the first three grand-slams and securing the year-end number one ranking for a record seventh time. But while other elite players must find the dominance of the big three daunting, recent results offer them hope.

In September Daniil Medvedev won his first major tournament by beating Mr Djokovic in the final of the US Open, denying the Serb a historic “calendar grand-slam” (winning all four slams in a year). Then on November 20th Alexander Zverev beat Mr Djokovic in the semi-finals of the ATP Finals, the prestigious season-ending finale (and went on to defeat Mr Medvedev in the final one day later). Are these victories a harbinger of better times for them and others on the tour?

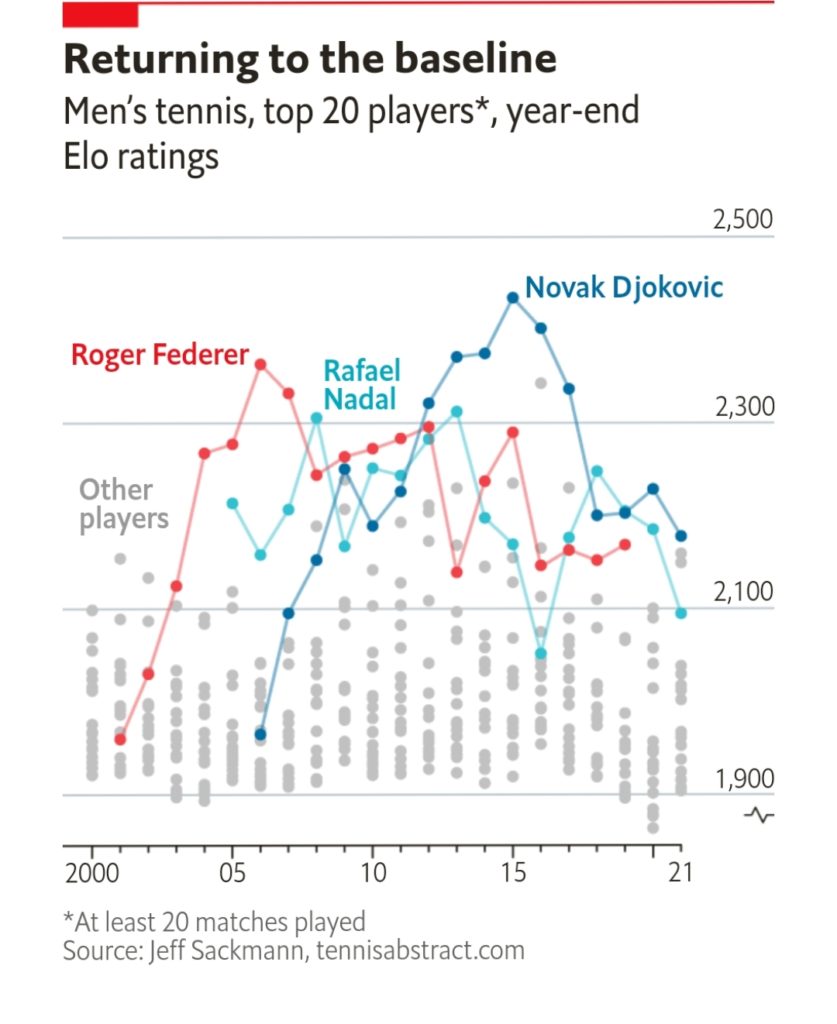

According to Elo, a system which rates players by their performance and the quality of opponents they face, Mr Djokovic’s rating at the end of 2021 was 2,178 points, his lowest in more than a decade and just 19 points higher than the second-ranked Mr Medvedev. Last year the gap between the pair was 128 points.

More tellingly, the gulf between Mr Djokovic and players lower down the ranks is narrowing too. In 2015, after arguably the greatest year in tennis, Mr Djokovic registered an Elo rating of 2,434, which surpassed the peaks of Mr Federer (2,363 in 2006) and Mr Nadal (2,312 in 2013). The gap then between Mr Djokovic and the 20th Elo-ranked player was 515 points, the highest it has been in the past twenty years. In 2021 that gap was down to 274 points, the lowest since 2003, when Mr Federer’s era of dominance was just beginning.

For a reminder of a more egalitarian era, look to the early 2000s. In the four years before 2004, 11 different players won a grand-slam, but it took another 17 years to have 11 different winners again. Such variety is a boon for fans who crave uncertainty and love the underdog. But devotees of the big three, and of the supreme quality of tennis that they produce, will rue their fading dominance.

By The Economist