Undermined by the pandemic and a deepening economic crisis, and surrounded by sycophants, Aleksandr Lukashenko badly miscalculated in the recent election.

MOSCOW — The autocratic leader of Belarus, never a stickler for accurate vote counting, boasted early in his 26-year rule that he was so popular that he had to falsify his share of the vote because the original number — 93.5 percent — was too implausibly high. He said he made it 86 percent instead.

“Yes, we falsified the last election,” the leader, Aleksandr Lukashenko, said after winning his third term as president in 2006.

On Sunday, Mr. Lukashenko, known as “Europe’s last dictator,” claimed yet another victory, his sixth, in yet another presidential election marred by faulty arithmetic, this time to give him an implausible landslide victory with more than 80 percent of the vote.

But instead of celebrating triumph in what should have been just another routine rite of popular affirmation, Mr. Lukashenko is fighting for his political life, besieged by protests across his country and a tsunami of international criticism.

“He has been falsifying elections for decades. He can’t help himself but this year is different,” said Andrei Sannikov, a former Belarusian diplomat who ran against Mr. Lukashenko for the presidency in 2010

Protesters took to the streets of Minsk on Monday. M

Continue reading the main storyhttps://8f854eea906e3b3ce13fb6c7cd082506.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-37/html/container.html#xpc=sf-gdn-exp-5&p=https%3A//www.nytimes.com

This well-rehearsed charade, however, came unstuck this year.

In the weeks leading to the election, Mr. Lukashenko so badly bungled the coronavirus pandemic, telling his citizens to protect their health by riding tractors, drinking vodka and taking saunas, that even some of those who genuinely liked him began to wonder whether it was time for a change. A deepening economic crisis, exacerbated by the end of cut-price deliveries of oil and natural gas from Russia, further undermined the president’s grip.

“Lukashenko has not been doing anything new this year, but people started seeing him in a new way,” said Maryna Rakhlia, a Belarusian expert at the German Marshall Fund in Berlin.

His what-me-worry response to the coronavirus, which left Belarus with one of Europe’s highest per capita infection rates, shattered Mr. Lukashenko’s ability to impose his own alternative reality, Ms. Rakhlia said. “This was the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

With the opposition’s main leader, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, forced to flee Belarus on Tuesday to neighboring Lithuania and Mr. Lukashenko’s security apparatus showing no sign of wavering in its support for his government, the president may survive the current storm. But he has lost the aura of an invincible popular leader.

Frank Dikotter, a Dutch academic and author of “How to Be a Dictator,” a study of modern autocrats, said in a telephone interview that leaders like Mr. Lukashenko struggle with the fact that “we live in a democratic age and they all need ballot boxes to show that people really do adore them.”

Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, Mr. Lukashenko’s challenger, at a campaign rally in August. Mrs. Tikhanovskaya left Belarus on Tuesday for neighboring Lithuania. Tatyana Zenkovich/EPA, via Shutterstock

This craving for popularity, either real or fabricated, leaves modern dictators far more vulnerable than past tyrants like Stalin or Mao Zedong, who never allowed voters even a minimal semblance of choice. “The problem for all today’s dictators in the long term,” Mr. Dikotter said, “is that they are surrounded by sycophants and, sooner or later, they make a fatal mistake.”

Mr. Lukashenko still controls an extensive, so far loyal and shockingly brutal security apparatus. Riot police officers in recent days have displayed extraordinary force against protesters, pummeling demonstrators as they lie on the ground, firing volley after volley of rubber bullets and stun grenades into peaceful unarmed crowds and arresting thousands of people, many of them simply for being outside.

“We used to trust him before, but life was getting worse and worse with each day,” said Valery, a mechanic at a state-owned engineering company in Minsk, the capital of Belarus, who declined to give his name for fear of punishment. “What is happening now is complete lawlessness. There was no election, it was a sham. I used to be loyal, I knew that there needed to be law enforcement to fight against criminals, bandits. But these are people, who can go against their own people?”

Before the election, as criticism of his handling of the pandemic grew and helped trigger protests by tens of thousands of people, the biggest since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Mr. Lukashenko warned darkly that Belarusians should remember the notorious 2005 Andijan massacre in Uzbekistan, when security forces loyal to the Uzbek leader, Islam Karimov, shot hundreds of protesters dead.

Disinfecting a hospital ward in Minsk amid the coronavirus pandemic in May. Mr. Lukashenko what-me-worry response to the coronavirus left Belarus with one of Europe’s highest per capita infection rates. Tatyana Zenkovich/EPA, via Shutterstock

“Dictators live in their own bubble and that is their problem,” Mr. Dikotter said. “They have to make all major decisions but have no real information.”

Speaking in Minsk on Wednesday, Mr. Lukashenko dismissed the protesters, who have included young professionals as well as pensioners, as “people with a criminal past who are now unemployed” and told them to get jobs.

In recent weeks, as it became evident that this year’s election results would require more than the usual level of falsification to secure the required result, Mr. Lukashenko thrashed out not only against his usual critics in the West but also against his longstanding ally and principal patron, Russia. Late last month, his security agents arrested what they claimed were 33 Russian mercenaries sent by Moscow to disrupt the election.

President Vladimir V. Putin still congratulated Mr. Lukashenko on his election victory, one of the few foreign leaders to accept the results at face value. But others in Russia, even those prone to paranoid conspiracy theories about the West, have questioned Mr. Lukashenko’s fitness to govern.

Konstantin Zatulin, a prominent member of the Russian Parliament well known for seething over Western plots, this week described the Belarus election as a “total falsification,” saying that the official results “are not credible.”

He said Mr. Lukashenko, whom he described as “insane,” had “exceeded all limits.” The problem, he added, “is that the leader of Belarus is a deranged person when it comes to power.” Moscow Komsomolets, a popular Russian newspaper not known for championing fair elections, gave its own blunt verdict in a headline this week: “Lukashenko has Turned Into a Despised Dictator.”

President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia and Mr. Lukashenko meeting last year. Mr. Putin congratulated Mr. Lukashenko on his election victory but others in Russia have questioned Mr. Lukashenko’s fitness to govern. Mikhail Klimentyev/Sputnik, via Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Mr. Lukashenko’s longtime Belarusian critics have been saying such things for years, but it is extremely rare for a Russian politician long known as a friend of Belarus and a Moscow newspaper to declare the country’s leader a power-mad lunatic.

In the past, Mr. Lukashenko could always be confident that Russians shared his view that elections were something of a joke. Joshing around with a group of Russian visitors to Minsk in 2006, he drew howls of laughter when he told his story about lowering his share of the vote.

The joke, however, has turned deadly serious. There is now a wide consensus among Western governments and many Belarusians that he falsified Sunday’s results to increase his own count and dramatically reduce that of his principal opponent, Ms. Tikhanovskaya.

Assessing the true level of support for Mr. Lukashenko or his opponents is all but impossible. Independent polling of public opinion is mostly illegal and surveys carried out by pollsters affiliated with the government are usually kept secret.

But Mr. Lukashenko’s claim to have won four-fifths of the vote on Sunday clashed starkly with the leaked results of an opinion poll by the Belarus Academy of Sciences in April. They showed that only about a third of the population trusted Mr. Lukashenko, far below the portion of the vote he supposedly received on Sunday.

That result — delivered by Lidya M. Yermoshina, a veteran Lukashenko loyalist who has headed the Central Election Commission since 1996 — has made Ms. Yermoshina the butt of dark political jokes.

One joke now making the rounds in Belarus has Ms. Yermoshina traveling to the United States to help President Trump win re-election in November. After the vote, she reports back to Mr. Lukashenko that her mission has been a success: “Congratulations! You have just won a landslide in America.”

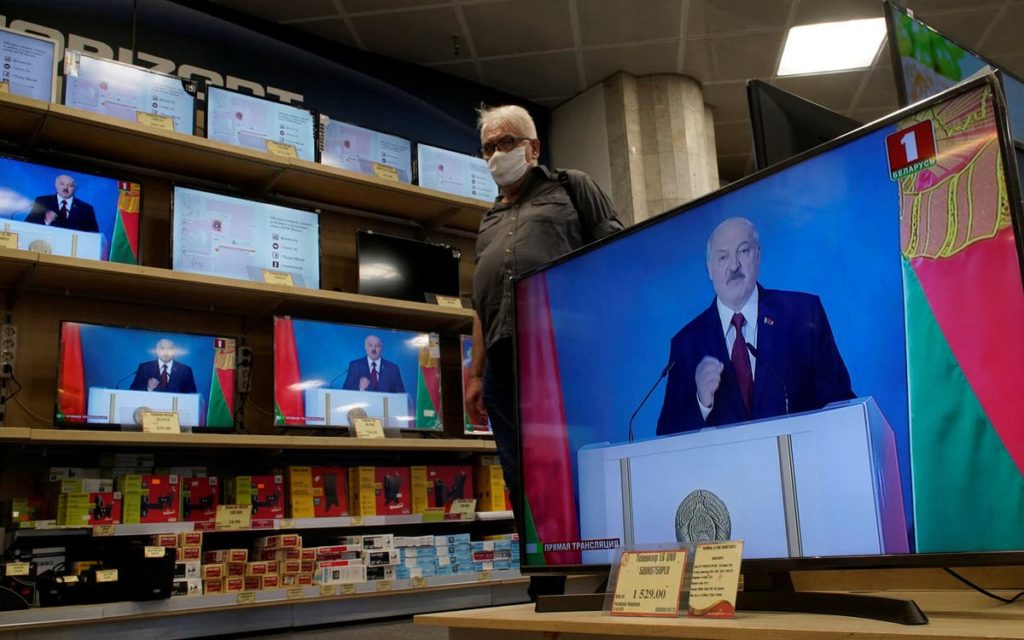

FEATURED IMAGE: On Sunday, Belarus’s leader, Aleksandr Lukashenko, known as “Europe’s last dictator,” claimed a sixth victory in a presidential election that critics called rigged. Vasily Fedosenko/Reuters

By Andrew Higgins/ The New York Times