LONDON — Jorginho stood in front of the massed ranks of Italy’s fans, straightened his back and took a breath. Every single one of them knew what was coming. So, too, did Unai Simón, Spain’s goalkeeper, fidgeting and flickering with nervous energy on his line.

There is an inevitability about Jorginho and penalties. He approaches the ball in a gentle trot. Halfway there, he performs a little hop, a brief stutter designed to entice the goalkeeper into shifting his feet. That almost imperceptible movement, that slight twitch, is all Jorginho needs. That is the point when he knows which side of the net will prove to be out of reach for the goalkeeper.

From there, it is simple. It looks that way, certainly, even under all the pressure of Tuesday’s Euro 2020 semifinal: a single strike of the ball, after two hours of sweat and thunder and tension, to send his team, his country, into the final. Except he does not strike it. He addresses it. He steers it. He caresses it. It is the same every time. But just because you know something is coming does not mean you can do anything about it.

Italy has not played to the stereotype these last three weeks. It arrived at Euro 2020 in a curious position, unbeaten in 27 games, a run stretching back a couple of years, but not among the favorites. France, England, Portugal and Belgium were all under considerably more pressure. Whatever happened, Roberto Mancini, Italy’s coach, vowed that it would be “fun.”

He was as good as his word, for those first forays at least. Turkey, Switzerland and Wales were swept aside, imperiously, on home territory in Rome. Austria was, eventually, overpowered in the round of 16. A brilliant spell of 15 or 20 minutes took Mancini’s team past Belgium, officially ranked as the world’s best side. This was Italy stripped of the stress of expectation, and imbued with freedom.

But it was not that sense of adventure, that freshly inculcated and deliberately nurtured spirit of gioia di vivere, that allowed Italy to take the final step. Spain, even an iteration that remains a work in progress, was always likely to require a display of what might diplomatically be called more traditional Italian virtues: obduracy and indomitability, organization and guile, gritted teeth and strained sinews.

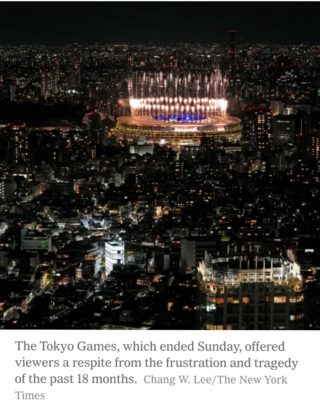

Fans watching the shootout at the Piazza del Popolo in Rome. Angelo Carconi/EPA, via Shutterstock

It may yet rank as Mancini’s greatest achievement, in his three years in charge of his national side, that he has managed to retain those traits while reducing Italy’s reliance on them. Giorgio Chiellini and Leonardo Bonucci, now well into the autumn of their careers, still greet blocked shots and pickpocket interceptions with the same innocent, unalloyed delight that they might have celebrated a well-orchestrated offside trap as children.

Where Mancini has triumphed is he has made that Italy’s option of last resort, rather than its whole strategy. His team would, generally, prefer to beat its opponents. But if that is not possible, then it is more than happy to live up to Johan Cruyff’s aphorism and make sure it does not lose to them.

And so, while this was not the sort of performance with which the new Italy might stir the soul, it was one of which the old Italy would be rightly proud. For all its possession of the ball, Spain was restricted to just a couple of chances in the first half. They came more frequently in the second, as Luis Enrique’s team chased an equalizer to Federico Chiesa’s opening goal; Spain seemed, at times, to be finding holes as quickly as Chiellini and Bonucci could plug them.

Gianluigi Donnarumma, right, punching a ball clear off the head of Álvaro Morata. Pool photo by Frank Augstein

But the best measure of Italy’s performance was, perhaps, the fact that the only goal that got through was sublime: a quicksilver one-two between Alvaro Morata and the live wire Dani Olmo and a calm, unerring finish from Morata. Chiellini stood, hands on his hips, as though his own personal pride had been stung. And then he dusted himself down and set about making sure it did not happen again.

It did not, of course, because no matter how much it has changed under Mancini, Italy is still Italy. Its midfield, so fluid in the opening five games of the tournament, snapped into scurrying and harrying mode, trying to disrupt Spain’s rhythm. Rafael Toloi came off the bench as a roving troubleshooter, involved in some sort of personal challenge to see how long he could go without getting a booking.

And all the while, Chiellini, in particular, seemed to be enjoying himself, relishing this little trip down memory lane. There were 60,000 people inside Wembley Stadium, the vast majority of them Italians biting their nails to the quick; there were 22 players on the field, all of them conscious that the slightest slip might mean everything they had worked toward might fall apart, and Chiellini was smiling and laughing and giving impromptu pep talks to his goalkeeper.

Perhaps, to some extent, it was gamesmanship — a sign to Spain that, no matter how much they huffed and puffed, this was nothing he had not seen before, that he was not yet out of his comfort zone, that there was only one way this was ever going to end. Just because you know what is coming, after all, does not mean you can do anything about it.

Spain’s Dani Olmo with Italy’s Rafael Toloi in extra time. Pool photo by Matt Dunham

Italy held on, then, because it was always going to, because underneath it all, no matter how much it has changed, Chiellini is still there, and so it is still Italy. Chiellini had a broad grin on his face as he and Jordi Alba, Spain’s captain, tossed a coin to see which team would go first in the penalty shootout, and Italy won. Then another, to see which end they would take them at: Italy won again. Chiellini broke into laughter, great peals of genuine laughter, at that, hugging Alba close. Italy had won twice already. He knew how this was going.

Manuel Locatelli might have missed, but then so did Olmo. And then, a few minutes later, Morata himself stepped up. He shot low, to Gianluigi Donnarumma’s left, and the goalkeeper scrambled over to paw it away, a devastating end to a tempestuous tournament for a player who has acted as a bellwether for Spain’s mood over the last month.

And so Jorginho began his long walk. He knew what he was going to do. The fans in front of him, their hands clasped in prayer, knew what he was going to do. Simon knew what he was going to do. He was going to send Italy to the final of Euro 2020. Just because you know what is coming does not mean you can do anything about it.

Jorginho, center, delivered the final blow, but Italy’s victory was a celebration of collective joy. Pool photo by Carl Recine

By Rory Smith/The New York Times