VLADIMIR PUTIN, so intent on bringing Ukraine under his control, is neglecting the problems facing Russians at home. A survey conducted between February 17th and 21st—that is, in the week before Mr Putin’s invasion—by the Levada Centre, an independent Russian pollster, found that 43% of Russians between the ages of 18 and 24 wanted to leave the country for good. And 44% of those who hoped to emigrate cited the “economic situation” as their motivation.

That situation is likely to get a lot worse. Western sanctions have created an economic storm: rising inflation, a crashing currency, and imports that are expected to dwindle. Many Russians will soon struggle to afford what they need to survive.

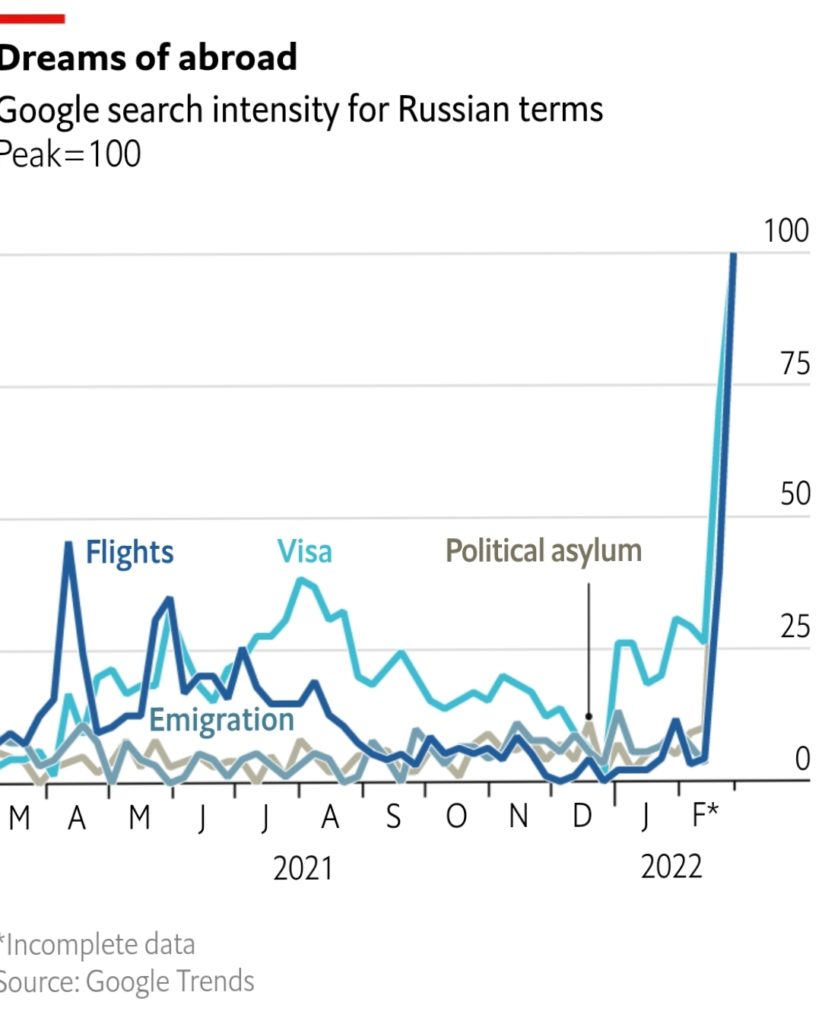

Eagerness to leave seems to be mounting. Data from Google Trends, which tracks how often particular words are entered into its search engine, show that Russian-language searches for “political asylum”, “emigration”, “flights” and “visa” all leapt in Russia in the days leading up to the invasion on February 24th. Queries for “flights” increased nine-fold from the week ending February 20th to the week ending February 27th. More Russians are asking Google “how to leave Russia” than have done so in 18 years since such data became public. Searches in the final two weeks of February were 16 times higher than the average weekly search volume from the past five years. Finnish trains from St Petersburg to Helsinki—which typically accommodate far fewer passengers than they have capacity for—have been packed with Russian travellers since February 27th. VR Group, a Finnish train company, told The Economist they plan to double the number of daily trains in order to address the growing demand from Russian passengers.

Since the imposition of stringent economic sanctions by Western countries last weekend, the Russian authorities have been straining to prop up the economy and the rouble, which has sunk to record lows against the dollar. The central bank has doubled interest rates. Russians—who have been queuing to take their money out of the banks—have been banned from leaving the country with more than $10,000 in cash. On March 2nd, Mr Putin’s cabinet offered preferential government mortgages and military deferment to information technology workers at Russian firms. But as the grip of sanctions tightens, such incentives may not be enough to keep more Russians from leaving.

By The Economist