The repression on February 28th marked a distinct escalation in violence by the army

SINCE FEBRUARY 1ST, when Myanmar’s army toppled its civilian government, thousands of Burmese—and sometimes hundreds of thousands—have taken to the streets every day to protest against the coup. The army has so far refrained from repressing the movement with wholesale bloodshed, as it did during previous periods of agitation for democracy in 1988 and 2007, when thousands were killed. But as the protests have persisted, the junta’s methods have been growing more brutal.

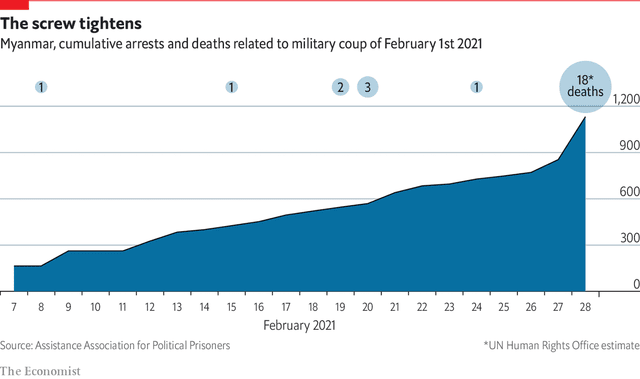

Soldiers began to counter the demonstrations a few weeks ago with water cannon and rubber bullets. Harsher measures, including the use of live ammunition, were limited to certain locations (notably Myanmar’s second city, Mandalay) and to attempts by the new regime to force striking workers to return to their posts. By February 27th a total of eight people had been killed, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), a local NGO. The bloodiest incident was an attack on employees of a shipyard in Mandalay who had downed tools and protesters who had gathered in solidarity: two of them died from injuries inflicted by the security services and several more were hurt.

The repression on February 28th constituted a distinct escalation in violence. Security forces fired into crowds in several cities across the country, including Yangon, the commercial capital, and Mandalay. At least 18 people were killed, according to the UN Human Rights Office, in what was by far the bloodiest day since the protests started. State-run media said that the authorities had detained 479 protesters during the course of the day. AAPP suspects that the true number of people arrested on February 28th was over 1,000, although it has not been able to document them all fully.

By The Economist