PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti — Gerard Lovius falls asleep at night on the floor of an empty classroom to the sound of gunfire. He and his shellshocked neighbors started living there a month ago, after gang members invaded his home, sending his terrified wife and three children running to the streets and leaving him with nothing: no money, no possessions, not even a cellphone.

On Tuesday morning, Mr. Lovius was back at his job as a street cleaner, tidying up before the day’s stately memorial for Haiti’s assassinated leader in the Champs de Mars, the capital’s main square. President Jovenel Moïse would soon be laid to rest, and the sparring members of his government had just reached a truce, vowing to lead the country anew.

But there was little peace in Mr. Lovius’s life. “We have hope only in God,” he said, hauling a wheelbarrow of trash up the street.

Gerard Lovius works as a street cleaner, but has not been paid for months. Federico Rios for The New York Times

Haiti’s leaders have called the political truce a new chapter, a historic turning of the page that, in the words of the interim prime minister, shows “that we can actually work together, even if we are different, even if we have different world outlooks.”

But for many in country, it does not seem like a change. The list of cabinet ministers published in the government’s official gazette featured several familiar names from Mr. Moïse’s governing party, including the new prime minister and the new foreign minister, both of whom had been angling to take over since the president was killed.

“This is a provocation,” Pierre Espérance, the executive director of the Haitian National Human Rights Defense Network, said of the party’s control of the new government. “It means the crisis will continue, insecurity will continue, and the gangs will continue.”

He argued that Mr. Moïse was a victim of his own rule, a leader who “died because of the insecurity his party created.” Two years ago, violence and furious demonstrators condemning corruption and demanding the president’s ouster locked the country in place — keeping the sick from hospitals, children from school, workers from rare jobs and people in the dark in areas where electricity stopped flowing.

Gangs have become more brazen since then, controlling large parts of the capital, attacking at will, kidnapping children on their way to school and pastors in the middle of delivering their services.

“The country is going to remain in the same condition, unless they get their heads together,” Rosemane Jean Louis, said shortly before the memorial began and the new government took office. “We have no security. We are hungry. We are in misery.”

Ms. Jean Louis recounted how she had casually said goodbye to her son, 24, one day last year, not knowing it would be the last time. With a smile, he had grabbed a piece of candy from the pile of treats she sold outside their home, then continued on his way to meet a friend. He made it a block, she said, before being shot dead by gang members in front of a church.

“I didn’t even find his body,” said Ms. Jean Louis, 61, tears falling. “They took it with them.”

Crime, kidnappings, gangs, security: the words streamed from Haitians across the capital as dignitaries paid their respects to the assassinated president on Tuesday and his successors took the helm. Even as rival politicians made claims and counterclaims to replace Mr. Moïse, residents were still in the streets protesting — often because they felt certain that their new leaders, whoever might prevail, would not care about them.

“There is too much kidnapping in this country,” said Steve Madden despairingly, standing in a cluster of men last week in a stare-off with the police.

Where Avenue John Brown spills out from a lush valley into the gritty streets downtown, tires burned along the road as Mr. Madden and other residents gathered. A local port worker had been kidnapped the day before, and his frightened neighbors were demanding his return, Mr. Madden said. A phalanx of police officers stood nearby with large guns.

The streets of Port-au-Prince remain tense. Federico Rios for The New York Times

Whole areas of the capital are too dangerous to drive through.

The Champs de Mars, once a place where people danced en masse during carnival and assembled on hot nights to eat ice cream or share a beer with friends, has been largely desolate since the assassination. Across the street from the presidential palace, still not replaced after the earthquake more than a decade ago, a small clutch of wilted flowers and candles sat in a clump for Mr. Moïse. A large portrait of him, with tears rolling down his face, had fallen on the ground. The words “I tried, don’t you give up, continue the fight” were printed on it.

Kim Baptiste Jean-Louis, 32, rushed over to set the picture right on an easel. When asked if he had been a fan of Mr. Moïse, he shrugged. “But,” he said, “he was the president.”

Mr. Moïse’s memorial took place in the garden of the Museum of the Haitian National Pantheon, where the anchor of Christopher Columbus’s ship, the Santa Maria, is on display, along with the chains of former slaves.

Guests came in slowly, including the two men who wrestled to succeed the president: Ariel Henry, the neurosurgeon appointed prime minister right before Mr. Moïse was killed, and Claude Joseph, the interim prime minister who was being replaced that week but quickly took control of the government and imposed a “state of siege.”

Eulogies for Mr. Moïse, whose “increasingly authoritarian” rule had alarmed many in and outside Haiti, portrayed him as a warrior for social justice who fought the country’s oligarchs, a crusader whose reputation had been assassinated before he was. Diplomats and ministers in his government assembled beneath a trellis covered in bougainvillea, including at least one official in the Moïse administration who had been sanctioned by the United States in connection with a 2018 massacre.

“You can kill a revolutionary, but you can’t assassinate the revolution,” Mr. Joseph said at the memorial.

The power struggle between Mr. Joseph and Mr. Henry had officially been settled. Mr. Joseph said Monday that he had agreed to step down and serve as minister of foreign affairs and religion, while Mr. Henry became prime minister, paving the way for elections in the future. The two men stood next to each other at the start of the ceremony, shoulder to shoulder, flanked by members of Mr. Moïse’s cabinet.

Soon after the memorial, the new government was installed under an awning in front of the prime minister’s office. Mr. Joseph said he was handing the baton to Mr. Henry, who spoke at length of the terrors that had gripped the nation, the people who had been killed and robbed, the homes and businesses looted and burned. He promised to restore stability and prepare for elections. The two men hugged briefly.

The show of unity on Tuesday followed a contentious scramble for power. Lawmakers and democracy advocates condemned Mr. Joseph’s quick grasp of the national reins and his imposition of a state of siege right after the killing, with some likening it to a coup.

The president of the Senate, Joseph Lambert, said he was going to be sworn in as Haiti’s new leader instead. Then he abruptly postponed that move, explaining later in an interview that American officials, who have exercised enormous influence over Haitian politics since invading the country more than 100 years ago, had urged him to stand down.

Mr. Henry had also tried to assert his authority last week, with little success. He issued a news release promising to unveil his new cabinet at the Karibe Hotel, a landmark of the elite lined with palm trees that has been a favored spot for political announcements in the past.

But just as Mr. Henry’s news conference was supposed to start last week, the hotel manager shut the building’s heavy metal doors, blocking news organizations from entering. He had not been informed of the news conference ahead of time, he said, and didn’t want to be seen supporting one political faction over another.

“You know how sensitive things are here,” explained the manager, Patrice Jacquet. “I have to take measures to protect the hotel.”

For many Haitians, the political maneuvering was just that — a power play by members of the elite and the governing party that promised them little relief. Some remembered the president fondly and mourned the loss of a politician who painted himself as an enemy of the nation’s entrenched interests.

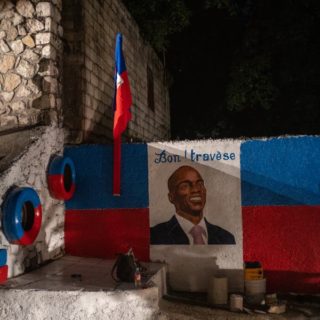

A newly painted portrait of President Möise in Port-au-Prince. Federico Rios for The New York Times

On a wall a few blocks from the former president’s home, a group of artists finished a mural of Mr. Moïse on Monday evening. “He is the only president that cared,” said John Alfrena, 42, admiring the work, which had been done by his friends, while speculating that Mr. Moïse had been killed for taking on the country’s oligarchs, the small clump of families that controls much of the Haitian economy.

Now he hoped the president’s wife, Martine Moïse, would continue his political legacy.

“We will fight for Martine Moïse to become a candidate in 2022,” he said.

Mrs. Moïse surprised the country by returning on Saturday from Miami, where she had been treated for wounds she sustained during the attack on her husband. She emerged from the plane wearing a sling for her bandaged right arm and a bulletproof vest. Since then, she has largely remained out of sight, though a wrenching message was released on her verified Twitter account three days after the murder, mourning his death and encouraging the country to continue on his path.

“Twenty-five years of living together: In just one night, the mercenaries ripped him away from me,” the recording said. “Tears will never dry up in my eyes. My heart will always bleed.”

FEATURED IMAGE: Port-au-Prince this week. Federico Rios for The New York Times

By Catherine Porter/The New York Times