THE YEAR was 1972 and liberation was in the air. While Jane Fonda was in Hanoi beseeching American soldiers to stop bombing Vietnam, college students back home urged whoever would listen to make love, not war. What, exactly, it meant to make love in the age of sexual revolution, however, was anyone’s guess. For baby-boomers’ parents, sex was for procreation, and if it brought husband and wife closer together, that was an added bonus. At least, this was the orthodox view. Whatever went on in private was not openly discussed.

Yet the cultural reckoning which began in the 1960s and rolled through the 1970s scrambled that consensus. Armed with feminist manifestos and the contraceptive pill, wives challenged the prerogatives of their husbands in the bedroom. Group-sex enthusiasts at clothes-optional communes rejected the idea that sex must be contained by marriage, while gay men and women who “came out” defied heterosexual norms. As if all that weren’t radical enough, “Deep Throat”, the wildly successful hardcore film of 1972, thrust porn into the mainstream. Though feminists would later question who was actually liberated by the sexual revolution—and who was harmed—to many, it was a time of freewheeling sexuality.

Amid this chaos, Alex Comfort imposed some order. The British scientist hoped “The Joy of Sex”, first published 50 years ago, would do for sex what “Joy of Cooking” had done for food: equip readers with the basics and provide a “gourmet guide” for those seeking sexual satisfaction. His manual aimed to demystify sex and teach people how to enjoy it. After all, the idea that sex should be joyful was far from an obvious one at the time.

“The Joy of Sex” was a roaring success, selling tens of millions of copies, spawning five sequels and inspiring numerous spin-offs. The book’s popularity had a lot to do with its reassuring message. For years the belief that a lot of sex was sinful or deviant had gripped the Anglophone world, even as people frequented brothels and read smutty literature. Many people worried that their desires were somehow wrong or abnormal. In fact, wrote Comfort, as long as both participants enjoyed what they were doing, and did not hurt anyone, they had nothing to worry about. Though only mentioned once, he implied that consent is fundamental.

Riffing on the cooking theme, Comfort encouraged his readers to move from “starters” to “main courses”, served perhaps with “sauces and pickles”. Make a habit of nudity in the house, he counselled. Try oral sex (as Comfort noted, a “pretext for divorce on grounds of perversity” until the middle of the 20th century) and bondage, a “wild sexual sensation”. He wanted people to embrace their instincts: the man who could orgasm only in a bath of cooked spaghetti was certainly odd, but if it worked for him, then why not?

In contrast to the lifeless prose of sexologists and scientists, “The Joy of Sex” stood apart for its relaxed, approachable style and its emphasis on pleasure. It reads as if the author had written it on the sidelines of a love-in after smoking cannabis: the prose is salted with slang, gently humorous advice (“Never fool about sexually with vacuum cleaners”), and wacky claims about the erotic potential of unexpected body parts like the big toe (“a magnificent erotic instrument”).

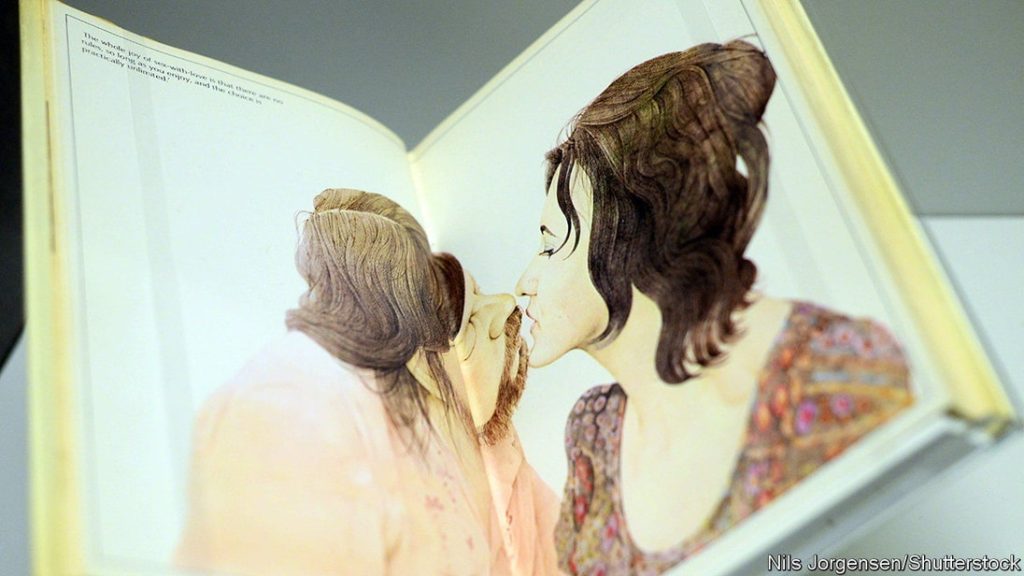

Comfort studied his subject in the wilds of free-sex communities such as Sandstone, a swingers resort in California. Gay Talese, an American writer, spotted Comfort there, sauntering nude between “prone bodies with the professional air of a lepidopterist strolling through the fields with a butterfly net”. And “with the least encouragement,” Mr Talese wrote, Comfort “would join a friendly clutch of bodies, and contribute to the merriment”; sometimes Comfort’s wife tagged along too. The Polaroids they took of their erotic adventures provided inspiration for scores of pencil drawings which were included in the book, which depict a couple locked in many different positions, sometimes with sex toys and always with fantastic tufts of body hair.

Comfort espoused relatively advanced ideas about sexual orientation, asserting that “we are all bisexual”. Yet his views were not so radical as to be off-putting to mainstream America. Good sex was not possible without love, he argued, and love requires “mutual tenderness, respect and consideration”. And even for an avowedly liberal man like Comfort, active homosexuality was beyond the pale. Bisexual urges should be channelled into fantasies within the confines of heterosexual partnerships, he wrote, for “being actively bisexual makes problems in our society”. Some of his advice for women is equally nauseating to a modern audience. “Don’t get yourself raped,” he advised his female readers.

“The Joy of Sex” displays the lingering conservatism of the era’s sexual politics and a revised edition has since omitted some offensive references. Despite those flaws, the book has aged well, not least for its illustrations. Comfort’s advice informed today’s sea of “sex positive” how-to guides. Partners who can communicate their desires to each other, he insisted, will shed feelings of shame and learn to have fun.