In early 1989, change seemed unstoppable in Beijing. That it wasn’t, that China would push back with fury, casts a large shadow over Hong Kong today.

On every June 4 since 1990, huge crowds of Hong Kongers joined in a vigil to remember the loss of lives, and the loss of ideals, in Tiananmen Square in 1989, when Chinese tanks and soldiers crushed a monthslong protest in Beijing calling for democratic changes to China’s one-party rule.

This year, for the first time, Hong Kong will not have the chance to officially remember an event it cannot forget.

The annual vigil was banned by the territory’s authorities, who said they were trying to curb the spread of the coronavirus.

But the outlawing of the commemoration for the only time in three decades comes when Hong Kong has been experiencing its own months of often-violent protests.

And it follows by only a few days a move by the Chinese Communist Party to approve a new law that will allow for the suppression of what it considers subversion, secession and seemingly any acts that might threaten national security in the semiautonomous city.

The ban on the vigil also arrives as China is trying to take advantage of the current chaos in the United States. Its goal is both to spread its influence globally and to tighten the internal grip of its authoritarian leader, President Xi Jinping.

Students and soldiers in Tiananmen Square in Beijing as protests began on April 22, 1989.Credit…Catherine Henriette/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Workers demonstrated their support for the student protesters in Tiananmen Square on May 18 that year.Credit…Catherine Henriette/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

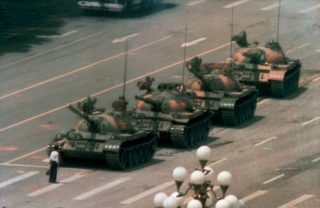

A protester in Tiananmen Square on June 5, 1989, captured the world’s attention and became known as the Tank Man.Credit…Jeff Widener/Associated Press

In early 1989, change seemed in the air. The Soviet Union was wobbling, and its Iron Curtain across Eastern Europe was beginning to show signs of cracking.

That spring, many hundreds of thousands of peaceful protesters — at first, mostly students, then a wide cross section of Beijing workers — gathered in Tiananmen Square in the capital.

With the protests applying intense pressure to the country’s leadership, and with the eyes of the world watching with mostly hopeful anticipation, the demonstrators’ calls for democracy appeared poised to be realized.

Then, early in the morning of June 4, the Chinese government decided it would act, but not to meet protesters’ demands. Instead, it ordered the military to clear the square, killing hundreds, maybe thousands of protesters.

The memory of that massacre has faded, or at least lost its urgency, in much of the world. But not in Hong Kong.

A candlelight vigil in Hong Kong on June 4, 2019, to commemorate the protesters killed in Tiananmen Square.Credit…Lam Yik Fei for The New York Times

Thousands gathered at Victoria Park in Hong Kong last June for the 30th anniversary of the crackdown.Credit…Lam Yik Fei for The New York Times

The vigil had been an annual tradition in Hong Kong. There will be no vigil this year.Credit…Lam Yik Fei for The New York Times

The day after the crackdown produced one of the most indelible images in the history of visual journalism: a lone man in a white shirt standing in the way of four tanks.

At the Hong Kong vigils that followed, though, it was another iconic image from Tiananmen Square, this one more hopeful, that was often highly visible — the 10-meter-tall Goddess of Democracy, inspired by the Statue of Liberty, which had stood over the Beijing protesters and was smashed in the crackdown.

Year after year, the vigils in Hong Kong drew enormous crowds. Those attending were not only commemorating the deaths in Beijing but embodying the rights given them for 50 years in the 1997 handover agreement between Britain and China — freedom of assembly and a free press — which had always seemed fragile with an authoritarian giant next door.

Last year’s vigil was both particularly large and extra poignant; it came less than three months after the introduction of a bill in Hong Kong’s Legislature that would have allowed the extradition of criminal suspects to China. That bill, since withdrawn, incited the protests that have swept Hong Kong.

Police officers clashing with protesters in Hong Kong last week.Credit…Lam Yik Fei for The New York Times

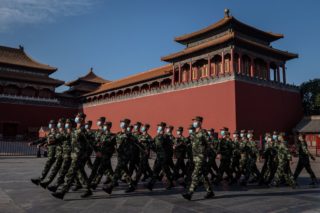

Paramilitary police officers marching in front of the Forbidden City in Beijing last month.Credit…Nicolas Asfouri/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

A view of Hong Kong’s skyline last week. People there are unsure about the future.Credit…Lam Yik Fei for The New York Times

Those protests, which raged last year, were largely curtailed by the coronavirus pandemic and the social distancing rules put in place to combat it.

Hong Kong in recent weeks has been emerging from its lockdown relatively unscathed, with only four reported deaths. The expectations were that the protests would pick up again.

But the threat posed by the new security law, which was condemned by the Trump administration, seems to have achieved one of its goals of diminishing the size and potency of the protests.

The banning of this year’s Tiananmen vigil underscored that Hong Kong’s freedoms are entering an uncertain phase.