Attempts to dress up authoritarian regimes as democracies are always bound to fail

MOST POLITICIANS find winning over a majority of the electorate challenging enough. Imagine, then, the difficulties of candidates in Myanmar, who must secure the approval not only of voters, but also of the army’s top brass. The National League for Democracy, the party led by Aung San Suu Kyi, a veteran dissident, excels at the first task. It has won the past two national elections by smothering landslides. But it is not so good at the second. On February 1st, as MPs elected at the most recent poll were about to take their seats, the army arrested them, and said that it would run the country instead.

Few outsiders had predicted the coup, despite the snarling statements emanating from the high command in the days beforehand, for the simple reason that the army was already in control of almost everything that mattered to it. Under the constitution, which the top brass itself foisted on the country, the army chief commands all the security services. He appoints his own boss (the minister of defence), as well as several other ministers and a quarter of MPs. That, in turn, gives him a veto over any attempts to change all this by amending the constitution. The system is designed to preserve the army’s interests, no matter what voters say they want. So why would the generals upend it?

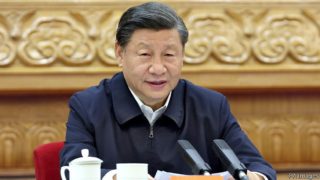

Putschists and despots tend to crave at least a veneer of legitimacy. A semblance of democracy may help keep their subjects quiescent and certainly makes international summits less awkward. The ideal is to create some scope for genuine political competition, the better to appease the masses and their foreign friends, while retaining control over all important decisions. The generals who run Pakistan and Thailand have attempted to devise such systems, as have the autocrats ruling Cambodia, Russia and Venezuela, among others. But few have been as explicit as Myanmar’s top brass about seeking to enshrine their authority in perpetuity in what otherwise resembles a democracy.

Such arrangements, however, are inherently unstable. Autocrats dislike being shown up, no matter how negligible the consequences. The regime of Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, this week jailed Alexei Navalny, a prominent critic, after he had the cheek to survive an assassination attempt, and to use his new lease on life to publicise a billion-dollar secret palace he says belongs to Mr Putin. In Myanmar Ms Suu Kyi was always careful to speak politely about the army, but her party repeatedly thumped the one backed by the generals, winning 12 times as many seats in the election in November. The snowflake generals found such humiliation hard to bear.

Unarmed politicians in Potemkin democracies naturally look for ways around the obstacles erected by the men with guns. Myanmar’s generals thought they had sidelined Ms Suu Kyi by barring her from the presidency, but she invented a new position, “state counsellor”, which she declared was “above the president”. Political parties in Thailand that are hostile to the top brass keep winning elections and trying to form governments, forcing the authorities to ban more and more of them.

That hints at the most unpredictable force disguised despots contend with: their citizens. They tend to vote for the wrong people (how many prime ministers must the Pakistani army have seen off?). If the system is hollow they can also take to the streets. In Belarus, after phoney elections, thousands have braved chilling repression. So too in Russia where, as Mr Navalny said this week, “lawlessness and tyranny pose as state prosecutors and dress in judges’ robes.”

Protests are also possible in Myanmar—as is their violent suppression. The army, after all, has quelled peaceful demonstrations by force plenty of times over the years. But the pariah status that comes with naked repression is precisely what the army was hoping to escape when it concocted the constitution it has just violated. In that sense, the coup, although crushing to Myanmar’s democrats, is a defeat for the generals, too.

By The Economist