Western admirers call Rwanda a model. Defectors paint a darker picture

KIGALI – RWANDA PREPARING to put on a show. The Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting begins on June 21st in Kigali, the capital. And if, despite the pandemic, foreign bigwigs come, President Paul Kagame wants them to be safe, comfortable and impressed.

Many will be. The streets are clean and quiet. Covid-19 masks are ubiquitous. Citizens form orderly queues to wash their hands outside shops. Some in quarantine are given electronic bracelets to track them. Tony Blair’s institute gushes about Rwanda’s early vaccine roll-out.

Some visitors may wonder, though, whether the discipline Mr Kagame imposes on this small, poor African nation goes too far. Police patrol the streets in trucks, rounding up curfew-breakers, who are often forced to spend a night in a stadium without food or water, listening to anti-covid slogans droned relentlessly over speakers. “I left my house to buy phone credit,” says Pierre, a middle-aged Kigali resident. “The police arrested me. It was two minutes before curfew and I explained that I lived in a house nearby. It was very cold in the stadium. There were no blankets.”

The streets have also been cleared of beggars, prostitutes and hawkers. Some of those arrested for “deviant behaviour” are taught to cook or sew. Others, according to Human Rights Watch, an ngo, are beaten with clubs. “The conditions were horrendous,” says Jean, a 16-year-old, who was detained for being homeless. “We slept on old mattresses teeming with lice. I have scars from the scabies.”

A furious debate rages about Rwanda and the man who runs it. Some say Mr Kagame is a hero: that he raised Rwanda from the ashes of genocide and turned it into the most orderly nation in Africa. Others say he is a tyrant whose brutality outweighs any development gains Rwanda has seen on his watch—and that those gains are in any case greatly exaggerated.

In the first camp are the Rwandan government itself, more or less everyone inside Rwanda who speaks openly, and a chorus of foreign admirers. In the second camp are human-rights groups and Rwandan exiles, including several former members of the regime. The debate is skewed by the fact that Rwandan dissidents live in constant fear of being murdered—even if they are far from home.

In February Seif Bamporiki, an organiser in South Africa for the Rwanda National Congress (rnc), an opposition group, was shot dead after being lured to a backstreet. It could have been a botched robbery. Violent crime is common in South Africa. But the gun had a silencer, which is unusual.

“He was one of my best friends,” says Serge Ndayizeye, who runs a pro-rnc radio station from America. “His death is not surprising,” he adds. “When you kill a leader, people will be afraid to join [the opposition]. We are fighting an evil man.”

Insiders who fall out with the regime are especially vulnerable. Seth Sendashonga, a former interior minister, was shot in Kenya in 1998. Patrick Karegeya, a former intelligence chief, was strangled in a hotel in South Africa in 2013. The government denies involvement in these attacks. But Mr Kagame appears to celebrate them. “You can’t betray Rwanda and not get punished for it,” he said after the murder of Karegeya, a former schoolfriend of his.

Mr Ndayizeye was attacked in Amsterdam in 2015, when he was reporting on a “Rwanda day” ceremony—when Mr Kagame meets the Rwandan diaspora. Assailants who spoke kinyarwanda, the Rwandan language, beat him up in the street. They took his phone; he tracked it flying back to Rwanda. Today he endures a barrage of threats on WhatsApp and Facebook. “Oh my goodness, it’s routine,” he says. They say things like: “You will die…like Patrick Karegeya.”

Mr Kagame’s reputation has taken a battering of late. A new book by a former journalist for the Financial Times, Michela Wrong, presents devastating evidence of his cruelty. A recent report by Freedom House, an American ngo, called Rwanda a global leader in intimidating its diaspora. It said the resources it devotes to this are “stunning”: phones are tapped, social media monitored and expatriates told that their relatives back home will be harmed if they speak out. Rwanda’s ambassador to Britain dismisses those conclusions, and says it makes no sense to accuse the government of disregard for human rights when it has progressed so far towards gender equality and environmental sustainability.

The regime has also attracted unwelcome publicity by kidnapping someone famous: Paul Rusesabagina, who was portrayed in the film “Hotel Rwanda”. Mr Rusesabagina (pictured on the previous page) saved hundreds of Tutsi lives during the genocide. He initially supported Mr Kagame, but now calls him a tyrant and once appealed for armed struggle to overthrow him. Rwanda calls him a terrorist. The government tricked him into boarding a jet to Kigali, where he was arrested. He will not get a fair trial: a video aired by Al Jazeera showed that the regime has intercepted his communications with his lawyers. “Kidnapping my father was a message to anyone who dares to speak up against [Mr Kagame], that they can get to them, too,” says his daughter, Carine Kanimba.

Untangling the truth about Mr Kagame’s extraordinary career is not easy. Neither his regime nor his critics always tell the truth. But some facts are uncontested. He was born in 1957. His family fled an anti-Tutsi pogrom when he was a small child, and settled in neighbouring Uganda. As a teenager, he joined a tiny rebel group—a few dozen men with 27 guns—which ended up overthrowing Uganda’s dictatorship in 1986. It was the first of at least three governments in three countries that Mr Kagame has had a hand in toppling.

His old rebel boss, Yoweri Museveni, became (and remains) president of Uganda. Mr Kagame served him as a director of military intelligence. There were many Tutsi exiles in the new Ugandan army, which paid and trained them. In 1990 most suddenly defected and invaded Rwanda to overthrow the Hutu dictatorship. Their leader was killed in the first week. Mr Kagame took over his forces, known as the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF).

The odds were stacked against him. The rpf said it was a movement for all Rwandans, but many Hutus, who were roughly 85% of the population, saw it as an invading Tutsi army. Still, Mr Kagame managed to seize control of part of the country. A ceasefire in 1993 left neither side satisfied. In April 1994 a plane carrying the Hutu president was shot down. (Who fired the missile is hotly disputed.) Hutu extremists, who had been stockpiling machetes, began a genocide of Tutsis.

In 100 days the army, Hutu militias and farmers slaughtered perhaps 500,000 people: mostly Tutsis, but also some Hutus who refused to take part. Mr Kagame stopped the genocide by shooting his way to power. He has run the country ever since.

Stopping the genocide was a great achievement. But some witnesses add details at odds with the monochromatically heroic tale taught in Rwanda today. Ms Wrong spent years interviewing members of the rpf who have fallen out with their leader. They describe a man both brilliant and astonishingly ruthless.

As a guerrilla in Uganda, he was a master of counter-intelligence, carrying a stick, not a gun. To get rid of a troublesome local government chief, he had a letter drafted thanking him for his help, signed by rebels. The man was executed by his own side. Mr Kagame was also in charge of weeding out traitors. If two rebels who were chatting fell silent when a third appeared, this could be taken as evidence that they were plotting, an ex-rebel told Ms Wrong, requesting anonymity. Some were executed with a single blow to the head with a short-handled hoe, which could also be used to scratch a shallow grave.

During and shortly after the civil war, rpf fighters massacred tens of thousands of Hutus in Rwanda, according to a suppressed un report. After Mr Kagame seized power, some 2m Hutus, including many guilty of genocide, fled into Congo (then called Zaire). Some launched raids back into Rwanda. Mr Kagame invaded Congo to crush them, and slaughtered tens of thousands more.

Congo’s dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, sheltered the génocidaires. So Mr Kagame’s men marched 1,000 miles across a country 89 times Rwanda’s size and overthrew him. In his place they installed a corrupt Congolese guerrilla, Laurent Kabila, and when he refused to take orders from Kigali, they invaded again. The resulting war sucked in several neighbouring states and cost somewhere between 800,000 and 5m lives, mostly from war-induced disease and hunger. It degenerated into a scramble for Congo’s minerals, which continues today. Mr Kabila was shot dead by a bodyguard, who was then swiftly killed. No one is sure who ordered the assassination. But Karegeya, Mr Kagame’s late spy chief, told Filip Reyntjens of the University of Antwerp that it was Rwanda.

Mr Kagame’s apologists tend to focus on the order he has imposed on Rwanda, rather than the mayhem he uncorked in Congo. Some argue that his ruthlessness is necessary. Were he ever to relax his grip, they fear, Hutu extremists might once again try to eliminate Rwanda’s Tutsis.

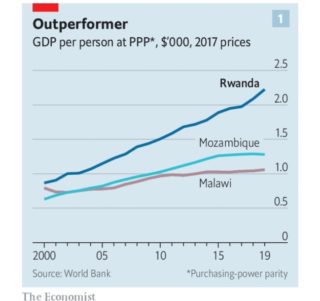

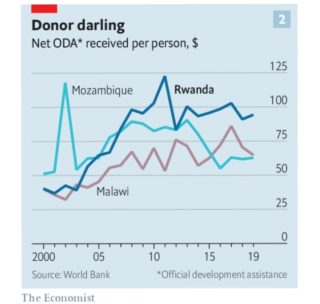

His economic record has also persuaded many donors to overlook human-rights abuses. Rwanda has received about 50% more aid per head than other similarly poor countries in the region such as Mozambique or Malawi (see chart 1). Donors view it as less corrupt and better at using aid to kick-start growth than messier democracies. At first glance, the data bear this out (see chart 2). In the 15 years to 2019, before the pandemic struck, Rwanda posted annual average growth in gdp of almost 8%. This was double the African average. Granted, Rwanda started from a very low base—the economy shrank by more than 50% immediately after the genocide. But the imf thinks it has still grown much faster than might have been expected.

“Rwanda’s track record, while not perfect, can be seen as one of the best—if not the best—examples where international aid has been effective,” argues the imf. Whereas in some countries donors’ cash has slipped into politicians’ pockets, in Rwanda much of it has been channelled into infrastructure. The results of this can be seen on Kigali’s skyline: dozens of shiny new hotels, a brightly coloured conference centre and an efficient airport.

Mr Kagame’s civil service is effective and reasonably meritocratic. Jobs are advertised and applicants sit fair exams (though many Hutus still feel that the plums go to Tutsis). Since 2014 Rwanda has come first in sub-Saharan Africa on the World Bank’s annual ranking of the quality of countries’ policies and institutions.

According to official statistics, the pay-off for Rwandans has been large. The poverty rate fell by seven percentage points between 2011 and 2017. Since 2000 the shares of mothers dying in childbirth, and of infants dying, have gone from the worst in east Africa to the best.

Disputed numbers

There are worries, however, that some numbers have been manipulated. After the global financial crisis of 2008, Mr Kagame insisted that Rwanda should report improbable gdp growth of 11%, recalls David Himbara, a former economic adviser. Mr Himbara quit soon after, and now lives in exile and in fear. The imf quietly estimated that Rwanda’s growth that year was 1.7%.

Some academics note a discrepancy between consumption per person in the national accounts (which are used to calculate GDP) and calculations based on surveys. In theory both numbers should move in tandem, since they are different ways of measuring roughly the same thing. But since 2005 Rwanda’s figures have diverged, with surveys showing that consumption has stagnated, despite seemingly impressive gdp growth. Some economists reckon that the gap between the two had widened to about 50% by 2013. The government says its figures are sound.

Rwanda’s reduction in poverty has also been questioned. The government employs a lower poverty threshold than most other countries. Using the international threshold of the equivalent of $1.90 per day, 56% of Rwandans were extremely poor in 2017, says the World Bank; by the government’s measure, 38% were. Mr Reyntjens reckons that much of the official reduction of poverty is due to a change in the way it was calculated. In 2011 Rwanda’s poverty line was based on the cost of buying a basket of food that accurately reflected what poor Rwandans ate. In 2014 it reduced the poverty threshold by 19% by selecting a different basket, with the same number of calories, that they might in theory buy. Had it not changed the basket, its calculations would have shown that poverty actually rose over that period, rather than falling.

Not all outsiders agree. Phil Clark of the School of Oriental and African Studies in London thinks that the economists arguing poverty has increased are “categorically wrong”. “Anyone who’s really looking at Rwanda over the last ten to 15 to 20 years, particularly going out into the countryside, is just struck by how better-off people are than they were at the end of the 1990s or in the early 2000s,” he says.

Whatever happened in the years up to 2014, there is now a consensus that progress has, if not ground to a halt, at least slowed. The World Bank reckons that between 2014 and 2017 the share of Rwandans who are poor was stagnant. This was partly because of government policies that discourage people from moving to cities and taking informal jobs, where they would earn more than by staying on the farm, even if they did make the streets noisier.

The outlook for economic growth is also grim. The pandemic has crushed tourism. Aid, which was worth 17% of gdp in the fiscal year ending 2006, had fallen to less than 10% last year. Public debt as a share of gdp has been shooting up—from 26% in 2013 to a projected 70% next year. Despite improvements in rankings such as the World Bank’s ease of doing business index, Rwanda has struggled to attract much investment. This is partly because its economy is too small to excite multinationals, but also because the ruling party has a habit of muscling in and demanding shares in successful firms started by Rwandans.

Mr Kagame’s intolerance of dissent surely affects the quality of advice he receives. Aides are jumpy. Mr Himbara says he saw Mr Kagame (pictured below) flog his finance director with a cane over a trivial problem involving curtains. Karegeya recounted a conversation from 2003, when Mr Kagame was running for election against a moderate Hutu who has since fled to Belgium. Karegeya suggested that Mr Kagame should claim to have won 65% of the vote—a solid win, but not ridiculous. The army chief said, no, he should claim 100%. The official tally gave him 95%. Karegeya was later jailed for insubordination; he defected soon after he was released.

The hard man of the hills

How popular is Mr Kagame? It is impossible to say. One ruling-party agent watches each cluster of ten households. “They know who came to visit you at night. They know what you ate,” says Mr Ndayizeye, the opposition radio host. In public, Rwandans repeat the official line that there are no Hutus and Tutsis any more, only Rwandans. But do they believe it?

Odette fled Rwanda in 1994 when she was 11. She has lived in a tarpaulin shack in a refugee camp in Congo ever since. She tried to return home in 2017, but found that her family’s farm was occupied by a politician. “When I told him I wanted the fields back…he threatened to kill me,” she says. “I was scared to go to the Ministry of Justice, as the Rwandan authorities always end up calling you a génocidaire.”

For all the rosy development statistics, Rwandans seem miserable. A global happiness survey in 2020 placed Rwanda 150th out of 153 countries, ahead only of Zimbabwe, South Sudan and Afghanistan.

Mr Kagame constantly shuffles his security team to make it harder for anyone to mount a coup. Opposition groups are scattered and disunited, ranging in ideology from peaceful liberals to violent bigots. Armed groups mount occasional terrorist attacks, but a un expert reckons there are only a few hundred former génocidaires left in the main anti-Rwandan guerrilla groups in Congo. “Obviously no armed group can walk on Kigali,” he says.

Under the current law, Mr Kagame could rule until 2034, when he will be 76. He could presumably change the constitution again to extend his time in office still further. He has offered no succession plan.

Nic Cheeseman of the University of Birmingham draws a worrying analogy with Ethiopia. Like Rwanda, it was run for many years by a clever, disciplined autocrat who kept a lid on ethnic antagonism and promoted economic development. However, after that strongman, Meles Zenawi, died in 2012, his successors could not hold the country together. Civil war has erupted, along ethnic lines.

“The main question facing authoritarian development in Africa has always been whether the economic gains achieved under repressive rule are sustainable,” Mr Cheeseman recently wrote. “Critics of this model worried that sooner or later, exclusionary political systems would face major challenges from marginalised groups and individuals, and that these challenges could undermine development plans. Recent events in Ethiopia suggest that these fears were well-founded.”

By The Economist