The politics of business • Inflation’s back • Vaccine fears • Myanmar’s plight

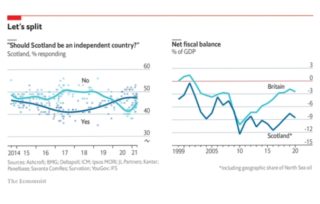

The union that binds the United Kingdom is weaker than at any time in living memory. The streets of Northern Ireland have been lit by riots and the reunification of the island of Ireland seems likelier than it has for decades. In Wales, support for independence is rising. Scotland voted in a referendum in 2014 to stay in the UK. But another, Britain-wide, vote in 2016 to leave the European Union, in which most Scots voted to remain, changed the terms of the argument, contributing to a surge in support for independence, despite its fraught economics. The reverberations of the Brexit vote have sullied the reputation of David Cameron, who was Britain’s prime minister at the time. It has been further dented by his involvement in a lobbying scandal.

Business and politics are growing closer in America. Corporate cash continues to flow into politics. But in recent years it is accompanied by a parallel stream of CEO activism, seen, for example, in a letter published on April 14th by hundreds of companies opposing legislation that makes it harder to vote. Chief executives claim that they simply have no choice but to tackle societal concerns because their customers, employees and shareholders demand it. But many disagree. The role of social-media giants is under particular scrutiny and Facebook faces a landmark test this month when its oversight board decides whether to reinstate Donald Trump’s account.

Inflation in America is still at modest levels, but it is back. The uptick is in part a statistical quirk, based on the comparison with a year ago, when prices were falling as the pandemic took hold. The Federal Reserve is rightly unworried by this cosmetic effect. Yet the central bank does have an inflation problem that will trouble it when the economic recovery produces sustained price pressures. Its studied ambiguity about its inflation target is adding to uncertainty. The strength of the recovery under way is showing through in soaring markets and sky-high profits at America’s banks.

Remarkably, America is close to delivering vaccinations against covid-19 to all who want them. Unfortunately, only seven out of ten Americans are interested. One of the largest vaccine-wary groups makes up about a quarter of the population: white evangelicals, or “born-again” Christians. It does not help that, with some vaccines, rare side-effects are emerging. China’s vaccination drive is also suffering some setbacks, with its Sinovac vaccine underperforming in clinical and real-world trials, and many in Hong Kong, distrustful of their government, unwilling to have it. India, the new centre of the pandemic, is vaccinating 3m people a day. To flatten the infection curve, it would need to reach 10m a day.

Since they seized power on February 1st, Myanmar’s generals have been unable to impose their will on the country, which is on the brink of collapse. They face the prospect of a united front between their many opponents among the country’s ethnic-Bamar majority and some of the minority-ethnic insurgencies they have been battling for decades. Myanmar risks becoming a failed state. There are parallels with Afghanistan, where the withdrawal of American troops in September, announced this week by President Joe Biden, may herald a new phase in a decades-long civil war. The nightmare is of Myanmar’s descent into the sort of bloodshed and chaos that has left half the populations in Yemen and Syria hungry.

By The Economist