NAIROBI, Kenya — President Emmanuel Macron of France arrived in the Rwandan capital, Kigali, on Thursday, in a symbolism-laden trip aimed at resetting relations after almost three decades of recriminations over his country’s role in the 1994 genocide.

The visit, the first by a French president since 2010, was aimed at writing “a new page in our relationship with Rwanda and Africa,” Mr. Macron said on Wednesday. It also represented an extension of Mr. Macron’s efforts to improve ties with the central African state and address France’s role in the genocide that left at least 800,000 ethnic Tutsis dead.

Both countries have released long-awaited reports in the past two months about France’s role during the bloodshed in 1994 that concluded that the European nation bore serious and overwhelming responsibility.

The findings washed away French denials that had poisoned relations for the past quarter-century, setting the stage for a series of quick developments, including a meeting between President Paul Kagame of Rwanda and former French Army officers during a visit to Paris this month, and now Mr. Macron’s two-day trip to Rwanda.

Mr. Macron, in a speech at the Kigali Genocide Memorial, where he also laid a wreath and observed a minute of silence, said, “France has a role, a history and a political responsibility in Rwanda.” He added: “It has a duty to confront history and to recognize its part of the suffering it inflicted on the Rwandan people by letting silence prevail too long over an examination of the truth.”

While Mr. Macron said that France was not complicit in the genocide and, as expected, did not apologize, he said, “I’ve come to recognize our responsibilities.”

During his trip, Mr. Macron is expected to inaugurate a French cultural center in Kigali, and attend a concert along with the Basketball Africa League quarterfinals. He also participated in a joint news conference with Mr. Kagame where the two leaders spoke about improving economic, political and cultural relations.

In his speech at the event, Mr. Kagame said the world should tackle “racism and genocide ideology” and said relations with France would grow stronger in coming years.

“President Macron is someone who listens and is committed to supporting Africa based on what Africa itself has chosen,” Mr. Kagame said. “This is different. It is better and it can last. Fundamentally this visit is about the future not the past.”

Mr. Macron, left, with President Paul Kagame of Rwanda in Kigali, the capital of the central African country, on Thursday. Ludovic Marin/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

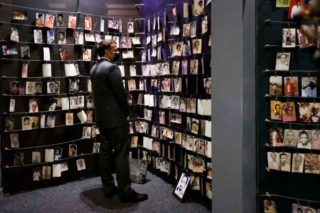

Mr. Macron’s visit to Rwanda’s main genocide memorial, where the remains of 250,000 victims are interred, was the fruit of a long, tortuous and fitful process of reconciliation between Rwanda and France. It was clinched by something far rarer: the achievement of a shared understanding, by an African nation and a former colonial power, of a monumental historical crime.

The visit is a win for Mr. Kagame, whose government in 2006 severed diplomatic relations with France over a case linked to the genocide. While diplomatic relations were restored three years later, tensions continued, and France has not had an accredited ambassador in Kigali since 2015.

Mr. Macron’s trip also comes as the Rwandan government faces renewed scrutiny over its human rights record, its campaign of assassinations and kidnapping of exiled dissidents and its long entanglement in conflicts in neighboring states.

France’s actions during the genocide, coupled with the inaction of the United States and other Western powers, had infuriated a generation of leaders in Rwanda and in the rest of Africa.

The Rwandan government’s report, published in April, stated that France played a “significant” role in “enabling a foreseeable genocide” and “did nothing to stop” the killings. In March, a report commissioned by Mr. Macron and written by historians, noted that France bore “overwhelming responsibilities” for the genocide, because it remained allied with the “racist, corrupt and violent” Hutu-led government even as those leaders prepared to slaughter the Tutsis. The report, however, cleared the French of complicity.

Establishing the historical truth could provide a base for a new relationship between African and Western nations, said Vincent Duclert, a French historian who led the commission that produced the report for the French government.

“A common history is now emerging,” Mr. Duclert said. “There must be equality. Europe can no longer explain to Africa what it needs to know. It’s up to Africa to explain to Europe what it’s doing.”

But the reconciliation is also the result of more prosaic calculations by Mr. Macron and Mr. Kagame, two leaders facing different kinds of pressures in Africa, where people are clamoring for more accountability, even as new and resurgent powers, like China, Russia and Turkey, are increasingly outmuscling old powers like France.

For Mr. Macron, a political disrupter at home who has sought to reset France’s relations with Africa, the reconciliation amounts to his most successful attempt at finding friends and business partners in new corners of the continent.

Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian of France, left, and his Rwandan counterpart, Vincent Biruta, met on Thursday. Ludovic Marin/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

But even though he said he did not want France “to remain prisoner of our past” in an interview with the magazine Jeune Afrique last November, he has often found that is exactly the case — embroiled, for example, in an increasingly unpopular, seven-year war against Islamism in West Africa that has forced him to look away from coups in allies, like Mali, and to work with longtime autocrats.

Last month, one of France’s most important allies in the war, Idriss Déby, who had ruled ruthlessly over Chad since 1990, was killed and replaced by his son Mahamat. In a tableau that recalled the bad old days of what was known as “Françafrique,” Mr. Macron was the only Western leader to attend the funeral and sat in the front row, next to the son, while other African leaders sat behind them.

“It’s a sepia image — Macron always tries to wipe away the past with a magic slate, but France’s history in Africa always catches up with him,” said Antoine Glaser, an expert on France’s relations with Africa and co-author of “The African Trap of Macron.”

FEATURED IMAGE: President Emmanuel Macron of France visited the Kigali Genocide Memorial in Rwanda on Thursday. “France has a role, a history and a political responsibility” in the African country, he said. Ludovic Marin/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

By Abdi Latif Dahir and Norimitsu Onishi/The New York Times