KINSHASA — I CONSIDER MYSELF to be like a mosquito,” says Bob Elvis, a musician, from his studio in downtown Kinshasa, the sprawling capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo. “I may be small but I can annoy you all night long, by singing, biting and not leaving you alone.”

Mr Elvis’s latest rap song, “Letter to Ya Tshitshi”, has rankled the president of Congo, Félix Tshisekedi, so much that it was banned days after being released. The song addresses Étienne Tshisekedi, the president’s dead father, a firebrand opposition leader, by his nickname. It laments his son’s incompetence.

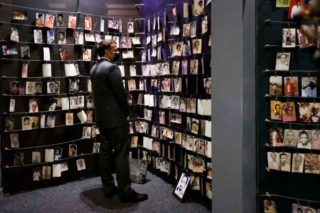

In the video, Mr Elvis raps to a photo of Mr Tshisekedi senior, surrounded by flickering candles. He repeats the refrain “since you left” and describes the country’s woes, from the scarcity of clean water to the abundance of corruption, electoral fraud and conflict. “Since you left, war in the east goes on,” he raps. “We are fighting for the rule of law.”

The Censorship Commission banned another six of Mr Elvis’s songs as well as a track called “What we have not done” by mpr, a hip-hop group. This song is about the failings of every Congolese president since independence. The ban on mpr’s track was rescinded a day later when fans kicked up a fuss.

Mr Elvis has not been so lucky. Broadcasters that play his forbidden tracks risk having their licences revoked. Other musicians have been targeted, too. A rapper from southern Congo, Sébastien Lumbwe, known as “Infrapa”, fled the country two weeks ago after being harassed by officials over his songs, which poke the government. “It is part of a pattern of shrinking civic space,” says Jean-Mobert Senga of Amnesty International, a watchdog. “It goes against President Tshisekedi’s commitment to respect human rights.”

The legal authority to ban the songs comes from a decree issued by a crooked dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, 54 years ago. The current president’s father, were he still alive, would be appalled. He spent much of his life campaigning against Mobutu’s champagne-gargling tyranny. Now his son is using the kleptocrat’s diktat to stifle dissidents of his father’s sort, albeit funkier.

Still, the Congolese government has not yet figured out how to make censorship effective in an age of social media. Although Mr Elvis says he is incensed by the ban, he is probably quite pleased about the buzz it has created. “Letter to Ya Tshitshi” has received more than four times as many hits on YouTube as some of his other recent tracks. It sounds tinnier played out of mobile phones than on the radio, but at least it is not a flop. Unlike the government that banned it.

By The Economist